EDWARD DE VERE,

17th EARL OF OXFORD

Dr. Michael Delahoyde

Washington State University

J. Thomas Looney, an English schoolteacher early in the 20th century for whom the Stratford myth seemed worse than unsatisfactory, went back to the start of the logical process. From the works themselves he constructed a list of traits that must have been associated with the true author:Looney found a perfect match in the Dictionary of National Biography when he read about Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. Looney published his discovery in 1920; unfortunately, therefore, some would like to dub this the Looney theory (though his name is pronounced Loan-ee, like Roosevelt). But Freud was convinced by it; Orson Welles was; Leslie Howard, Derek Jacobi, Jeremy Irons, Supreme Court judges, scholars, and more and more have been ever since.

- recognition of his genius

- eccentricity

- sensibility

- unconventionality

- inadequately appreciated

- literary recognition

- enthusiasm for theater

- recognition of his lyric poetry

- a superior classical education

- feudal connections

- aristrocratic

- connections with Lancastrian supporters

- enthusiasm for Italian culture

- enthusiasm for aristocratic sport (e.g. falconry)

- musicality

- financial improvidence

- ambivalence about women

- ambivalence about Catholicism

The de Vere family, originally from France, settled in England before the Norman Conquest. In 1066, Alberic (or Aubrey) de Vere sided with William the Conqueror and afterwards was rewarded with many estates. The youngest son of William, Henry, appointed de Vere the hereditary Lord Great Chamberlain of England -- involving duties associated with coronations. The fourth successive Aubrey in the 1100s was created Earl of Oxford. An Earl of Oxford was a favorite of Richard II (and therefore is excised from that history play), another was given a command at the battle of Agincourt, and Earls of Oxford supported the House of Lancaster in the Wars of the Roses in the 1400s. One accompanied Henry VII in 1485 and proved himself invaluable at Bosworth Field.

John de Vere, the 16th Earl of Oxford, with his first wife Dorothy Neville had a daughter, Katherine. In 1548 he married his second wife, Margery Golding, and had two more children, Edward, probably named after King Edward VI, and Mary. The 16th Earl was a patron of a polemical dramatist and of a company of actors known as Oxford's Men who would travel the country in summer and reside at Castle Hedingham in winter. Both the 16th Earl and the Countess of Oxford had court connections, John accompanying Princess Elizabeth from her prison to the throne and Margery being appointed a Maid of Honor. (Both, for example, seem to have spent 1559 at court.)

Edward de Vere was born in Essex at the de Vere ancestral home, Castle Hedingham, April 12, 1550 [o.s. (old style calendar) -- so we would place it later in the month and close to the traditional "Shakespeare" birthday actually]. (Some Oxfordians speculate that he may have been the earliest of Elizabeth's illegitimate children, born in 1548 and placed in the de Vere home.) John de Vere's wife, Margery Golding, the Countess of Oxford, was the half-sister of Arthur Golding, the scholar who would become one of Edward's tutors and who translated Ovid's Metamorphoses, which is acknowledged as the most influential work on the Shakespeare canon, or at least Shakespeare's favorite book. (Some speculate that a young de Vere was actually the translator, since Golding tended to exert his own efforts on religious tracts rather than anything with the spirit of Ovid.) Another uncle, Edward de Vere's paternal uncle Henry Howard, the Earl of Surrey, was one of the two originators (with Wyatt) of the sonnet form adapted from the Italian and today known as the "English" or "Shakespearean" sonnet form. Surrey also introduced blank verse with his Aeneid translations.

The young Edward de Vere was tutored in the household of Sir Thomas Smith. In 1561, the 16th Earl of Oxford entertained the 28-year-old Queen Elizabeth for five days at Hedingham. When the Earl's died in 1562, Edward de Vere, now the 17th Earl, became a royal ward and was sent to live with the Queen's Private Secretary and chief advisor, later Lord Treasurer, William Cecil, where his tutors included Laurence Nowell, and where he was surrounded by Cecil's impressive library. Cecil prided himself on his gardens too, maintained by England's premiere gardener, so horticulture was an important presence in the ward's upbringing. Oxford's daily routine for a time is preserved in a document showing that the day began at 7:00 with dancing instruction, proceeded with breakfast, French, Latin, writing, prayers, dinner; cosmography, Latin, French, writing exercises, common prayers, supper (Ward 20). Free time was to be devoted to riding, shooting, walking, and other "commendable exercises." Laurence Nowell eventually told Burghley, when de Vere was 13 years old, "I clearly see that my work for the Earl of Oxford cannot be much longer required."

The Countess de Vere remarried shortly after the 16th Earl's death, and no evidence survives that she and her son had any sort of relationship or even interest in one another. Her letters to Cecil regard financial matters only.

Edward de Vere received a B.A. from Cambridge University in August 1564 and an M.A. from Oxford University in September 1566. He undertook study of the law in February 1567 when he entered the Inns of Court, known also for its student theatrical performances. Oxfordians thus have an answer for how Shakespeare learned the law so intricately and its vocabulary so extensively. In 1569, a poet and translator, dedicating a work to the Earl of Oxford, wrote: "I do not deny that in many matters, I mean matters of learning, a nobleman ought to have a sight; but to be too much addicted that way, I think it is not good." Oxford was far too addicted to learning, according to English custom!

Frequently requesting commissions in foreign wars, he was allowed to accompany the Earl of Sussex in a Scottish campaign in 1570, probably serving on his staff. He and Sussex became staunch mutual supporters at court (parallel to Philip Sidney and his uncle Leicester). The older Sussex and Leicester had come to blows more than once in Council-chamber. Sussex served at court also in personally selecting plays to be performed; he superintended rehearsals too. When Sussex lay dying of consumption in 1583 (unless Leicester poisoned him), his last words were, "Beware of the Gypsy [Leicester]; you do not know the beast as well as I do" (qtd. in Ward 48).

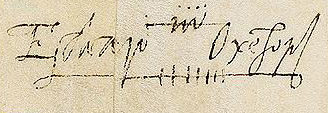

[Oxford is shown on the right in his role as Lord Great Chamberlain, carrying the sword of state before Queen Elizabeth.]

De Vere had a London dwelling and may in 1570 have studied astronomy under Dr. Dee. A 1584 dedication says of Oxford:

For who marketh better than heBurghley wrote to the Earl of Rutland in 1571: "And surely, my Lord, by dealing with him I find that which I often heard of your Lordship, that there is much more in him of understanding than any stranger to him would think. And for my part I find that whereof I take comfort in his wit and knowledge grown by good observation."

The seven turning flames of the sky?

Or hath read more of the antique;

Hath greater knowledge of the tongues?

Or understandeth sooner the sounds

Of the learner to love music?

(qtd. in Ward 50)Oxford was a favorite of Elizabeth's at court. He won tournaments, first in 1571, the same year he became engaged, with apparent misgivings (he seems to have become a runaway groom on the initial appointed wedding day), to a 14-year-old Anne Cecil, whose match with Philip Sidney (when they were 13 and 15) had fallen through. Cecil was made Baron, or Lord, Burghley at this time, and it is speculated that this honor was designed to make the bride worthy of the premiere Earl in the land. It is suggested that the courtship of Falstaff and Anne Page in The Merry Wives of Windsor parodies marriage negotiations between Anne and Oxford and onetime prospective husband Philip Sidney: the dowries and pensions match. (Also, the odd phrase "weaver's beam" in this play is underlined in de Vere's Geneva Bible: II Samuel 21:19.)

In 1572, Oxford seems to have tried a rescue attempt from the Tower for the condemned Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk -- de Vere's cousin who had been found guilty of a Catholic conspiracy against Elizabeth: the Ridolfi plot. In 1573, some of de Vere's friends and supposedly de Vere himself ambushed some travelers on the road from Gravesend to Rochester, an adventure nearly identical to a scene in Henry IV, Part 1: the Gadshill incident.

Elizabeth repeatedly turned down Oxford's requests for naval and military appointments. Testimony at court reads: "My Lord of Oxford is lately grown into great credit, for the Queen's Majesty delighteth more in his personage and his dancing and his valiantness than any other. I think Sussex doth back him all that he can. If it were not for his fickle head he would pass any of them shortly" (qtd. in Ward 78). He was known to Elizabeth as her "Boar" or her "Turk." Christopher Hatton was her "Sheep," counted among the social climbing court "reptilia" by Lord Willoughby. At one point in 1574, Oxford, without permission, bolted to the continent. Instead of finding himself in serious trouble for acting as if he were joining forces with the Catholics, he was summoned back by Elizabeth through a couple gentlemen pensioners she sent to retrieve him.

A year later, the 25-year-old Oxford was permitted an extensive tour of the continent: France, Germany, and especially Italy over the course of sixteen months. In Italy, he visited almost all of the Italian locations that later would provide the settings for Shakespeare's Italian plays. Mantua seems especially key to a number of Shakespeare/Oxford connections (esp. Lucrece and The Winter's Tale) and to Oxford's musical life.

During these travels, Oxford received word of his wife's pregnancy. He seemed joyful at the news in a letter to Burghley that survives and in his sending Anne extravagant gifts from overseas. But somewhere along the way his mind was changed against Anne and the Cecils. He became convinced that the child was not his and perhaps that the elder Cecils were worsening matters by loudly voicing outrage at the rumors. On the return voyage, Oxford's ship was attacked by pirates, which explains the extraneous bit in the autobiographically informed Hamlet (IV.vi).

On landing in England, Oxford refused to have anything to do with the Cecils. This estrangement from his wife lasted several years. The records show Burghley himself to be more anxious than outraged about this treatment of his daughter and grandchild. While Oxford was gone, An Hundreth Sundrie Flowres had been edited and republished, credited mostly to another court poet who was appointed Poet Lauriat. Meritum petere grave had been one of Oxford's poesies. Fortunatus Infoelix also appears in the collection (see Twelfth Night). Oxford's own poems from this time begin to lament the loss of his good name. Nevertheless, he was so taken with Italian culture during his travels that after his return he became known as the Italianate Englishman around court. He had presented Elizabeth with perfumed, decorated gloves, which became fashionable in England then, and the scent was for many years known as the Earl of Oxford's perfume.

Throughout the 1570s, Oxford provided entertainment for the Queen in the form of plays and served as a patron of acting companies and of writers such as John Lyly. George Puttenham later summed up artistic life at Elizabeth's court in The Arte of English Poesie (1589):

And in her Majesty's time that now is are sprung up another crew of Courtly makers [poets], noblemen and gentlemen of her Majesty's own servants, who have written excellently well as it would appear if their doings could be found out and made public with the rest, of which number is first that noble gentleman, Edward earl of Oxford.Another intriguing bit of praise to de Vere came from Gabriel Harvey in 1578: "Thine eyes flash fire; thy countenance shakes a spear; who would not swear that Achilles had come to life again?"1578 also saw the famous tennis-court quarrel with Philip Sidney, during which Oxford called the snotty Sidney a "puppy" in front of various French visitors. Elizabeth had to intervene later to stop Sidney's escalation of the incident into a duel. At another time, Oxford, probably irked at the treatment of Sussex, refused to dance on command of the Queen, insisting he would not do so for a bunch of Frenchmen. Rivals for the Queen's favor included Leicester, who was temporarily out of favor in 1578, and Christopher Hatton, the "dancing chancellor" called a "mere frippery" of a man and a sniveling sycophant, lampooned as Malvolio in Twelfth Night.

The Earl may have flirted with Catholicism, like many from the older established aristocratic families in England, but when it came to treason or worse against the Queen, he bailed. Late in 1580 he denounced a group of Catholic friends to the Queen, accusing them of treasonous activities and asking her mercy for his own, now repudiated, Catholicism. He was retained under house arrest for a short time, but Elizabeth characteristically prevaricated in the matter. The accused -- Henry Howard, Charles Arundel, and Francis Southwell -- retaliated by accusing de Vere in an absurdly long list of everything under the sun that would show him in a bad light: demonology, heresy, treason, homosexuality, "buggering a boy that is his cook and many other boys," such as one brought back from Italy, habitual drunkenness, declaring that Elizabeth had a bad singing voice, swearing to murder various courtiers, etc.

. . .Elizabeth, as usual, seems to have procrastinated and equivocated (until the Vavasour scandal turned her jealously against Oxford). The works of Shakespeare, including the Sonnets, are frequently concerned with themes of disgrace and decayed reputation. Indeed, most of this desperate material has colored the record against Oxford, even though these people were scum. Arundel eventually fled to Spain and put himself in the service of the King there. Oxford later insisted convincingly that "the Howards were the most treacherous race under heaven" and that "my Lord Howard [was] the worst villain that lived in this earth" (qtd. in Ward 117). Howard and his man Rowland Yorke had probably been behind the Iago-like whisperings into the ear of Oxford regarding his wife and first daughter back in 1576.

That the Catholics were great Ave Maria coxcombs that they would not rebel against the Queen;

My Lord of Norfolk worthy to lose his head for not following his [Oxford's] counsel at Litchfield to take arms;

Railing at Francis Southwell for commending the Queen's singing one night at Hampton Court, and protesting by the blood of God that she had the worst voice and did everything with the worst grace that ever woman did and that he was never nonplussed but when he came to speak of her;

Daily railing at the Queen, and falling out with Charles Arundel, Francis Southwell, and myself [Lord Henry Howard] in defence of her.

(qtd. in Ogburn and Ogburn 303; Ward 212-213)In 1581, the Queen learned of Oxford's affair with a Gentlewoman of the Bedchamber when the woman, Anne Vavasour (whose portrait suggests that she is the Dark Lady of the Sonnets) gave birth to a son (later Sir Edward Vere). Elizabeth sent de Vere, Vavasour, and the bastard infant to the Tower for a while. Afterwards, Thomas Knyvet, a Groom of the Privy Chamber and uncle of Anne Vavasour, fought Oxford; both men were wounded, Oxford more severely and in the leg, like Cassio in Othello, explaining the complaint of lameness in the Sonnets. Additional street fighting between Oxford's and Knyvet's servants, including some deaths, resemble the Montague/Capulet dynamics in Romeo and Juliet.

During the early 1580s it is likely that the Earl lived mainly at one of his Essex country houses, Wivenhoe, but this was sold in 1584. After this it is probable that he followed the court again and passed some time in his one remaining London house. Early in the 1580s Oxford's sister became engaged to Peregrine Bertie, Lord Willoughby. At first Oxford was against the match, but he and Willoughby became good friends. Despite the "Lord Fauntleroy" name, Peregrine Bertie was a man's man; Oxford's sister and Willoughby may have been the characters behind Kate and Petruchio in The Taming of the Shrew. Willoughby also was sent on embassy to the court at Elsinore, which may explain the source for some Danish details in Hamlet.

Oxford was banished from court until June 1583. The period seems to have seriously darkened his mood and turned his attentions largely from comedies to tragedies. He appealed to Burghley, who made a show of trying to speak to the Queen, but Burghley repeatedly put the matter in the hands of Hatton, Oxford's enemy and one who was simultaneously encouraging poetic ridicule of Oxford. Oxford also lost a small fortune in a northwest passage venture to Michael Lok (Shy-lock?). Hatton made out fantastically well in a similar enterprise.

But also in the early 1580s, Oxford reconciled with his wife Anne, and they had two more surviving children: daughters Bridget and Susan. Burghley at one point would be pushing for an engagement of the oldest daughter, Elizabeth, to Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton (a Shakespeare dedicatee and probably the "fair young man" of the Sonnets). The two other daughters were engaged and married respectively to the two dedicatees of the First Folio, the earls of Pembroke and Montgomery.

Oxford eventually returned into Elizabeth's good graces. In his thirties, Oxford controlled an acting company performing on tour and at court. He leased Blackfriars Theatre, and father-in-law Burghley complained of his "lewd friends."

Annuities from the crown averaged less than £20 (May 29), and courtiers typically were granted, if anything, lands and monopolies; but in 1586, the notoriously stingy Queen granted Oxford a £1000 annuity (= several hundred thousand dollars now). No explanation was given and the wording on the document was identical to the formula for the granting of secret service money. King James would continue this grant. Suspicion of course is that Elizabeth recognized the value and power of the theater and Oxford's task was to drum up English patriotism, especially in light of the growing Spanish threat. More than coincidentally, the vicar of Stratford Parish in Warwickshire, the Reverend John Ward, reported in his 1661-63 diary the local rumor that Shakespeare had "supplied the stage with two plays every year and for that had an allowance so large that he spent at the rate of £1000 a year, as I have heard." Hank Whittemore points out that Shakspere's Stratford cash estate amounted to no more than £350, and that the remuneration here is oddly called an "allowance" rather than an "income" ["A Year in the Life: 1586." Shakespeare Matters 2.4 (Summer 2003): 29-30].

In 1587, Thomas Kyd, now often credited as the author of The Spanish Tragedy, and often of the theoretical Ur-Hamlet, and The Taming of A Shrew, seems to have been in Oxford's employ. No records from his own lifetime record Kyd as being a playwright. John Lyly, another ostensible dramatist, left Oxford's employment in 1594 and never wrote another play in his lifetime. Despite his need for money, he never published the plays credited now to him -- because they were not his to publish? Anthony Munday was also in Oxford's employ.

Oxford sought a valiant command in the war with Spain. He decked out a ship for the purpose but between bad timing and Elizabeth's typical slightings, he probably saw little or no action during the Armada incident.

In 1588, the Countess of Oxford died. Three or four years later, in his early forties, Oxford married another of the Queen's maids of honor, Elizabeth Trentham, and moved to Hackney, near Stratford, the suburb north of London. The couple had a son, Henry, later the 18th Earl "who went on to become a leading nobleman in a bold, Protestant, anti-Spanish quadrumvirate of the 1620s, composed of himself and the very same noblemen to whom both the poems and First Folio of Shakespeare's plays had and would be dedicated: the 3rd earl of Southampton, the 4th earl of Pembroke, and the 1st earl of Montgomery" (Wright, "Who Was Edward de Vere?").

Oxford had lost fortunes and lands over the years. The Court of Wards bled him, but so did travel and, no doubt especially, his theatrical ventures prior to Elizabeth's grant. In the 1590s he sought additional monopolies and lands from Elizabeth, usually to no avail. The Forest of Essex was finally returned to de Vere ownership after a generation. Additionally,

When, after several years, feeling sufficiently established in his office, Hatton, in his role as Lord Chancellor, renewed his "attack upon his old enemy, the Earl of Oxford, by wrecking his theatrical company" and bringing about his serious financial embarrassment, the Queen made a sudden volte-face in the Earl's defense and "retaliated by vigorously demanding of Hatton what he had forced from Oxford, the payment of an enormous indebtedness, 'representing arrears of tenths and first-fruits,' amounting in all to 42,139 pounds, nearly twice the amount of Oxford's debts." This so unnerved Hatton that it was said to have aggravated his chronic diabetes and finally brought about his death in November 1591 -- just twenty years after he had accepted Dyer's cynical advice as to how to circumvent the Lord Great Chamberlain and supplant him in the Queen's favor. (Ogburn & Ogburn 705)"We believe that, in his forties and fifties, Oxford 'resolved' himself into his work, a distillation of the purest, best part of himself, called it 'Shakespeare,' and vanished" [Hughes, The Oxfordian 9 (2006): 7].

Burghley had been pushing earlier for a match between Oxford's daughter Elizabeth Vere and Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton. But 1595 saw the marriage of Elizabeth Vere to William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby, the wedding sometimes associated with the performance of A Midsummer Night's Dream. The in-laws visited each other with some frequency in the late 1590s, and, if Derby served as a new amanuensis for de Vere, this may explain why William Stanley was said to be "penning comedies for the common players" in 1599.

1598 saw the death of Lord Burghley and the first quarto publication of a "Shake-speare" play: Richard the Second. Francis Meres in Palladis Tamia mentioned "Shakespeare" for the first time as a playwright and Edward de Vere as being the "best for comedy amongst us."

Elizabeth died in 1603. Fortunately, James I was an enthusiastic Shake-speare fan. Unfortunately, Burghley's son Robert Cecil ran the government.

Although various oddities have given rise to much justified speculation about this, the record shows that Edward de Vere died in 1604, sometimes erroneously reported as having been by plague. The author "Shakespeare" was referred to in the past tense a few times after 1604. The outpouring of plays stopped; only a few "new" plays appear afterwards, and then lots for the first time in the 1623 Folio.

He wrote independently as an artist who chose his own subjects and themes, which coincided generally with the aims of the Tudor dynasty and the Protestant Reformation led by William and Robert Cecil. The Queen tolerated his often stinging wit and merciless humor and compulsion to hold the mirror up to members of her Court, including herself; but because this Hamlet-like earl told more truth than could be tolerated by the Cecils, whose tenure survived beyond Elizabeth's life, this true 'Shakespeare' was almost totally obliterated from history by the same English government he had expended his monumental talent, wisdom and energy to serve. [Hank Whittemore, "A Year in the Life: 1586." Shakespeare Matters 2.4 (Summer 2003): 30.]Contrary to some indications, his cousin Percival Golding later wrote that Oxford was eventually interred at Westminster. "A falsehood by Percival Golding in his never-published personal history of the Vere family would have served no useful purpose to anyone" (Altrocchi 9). "If Golding is correct, and if Edward de Vere, in fact, was the nobleman poet-playwright who called himself William Shake-speare, it is truly fitting that he -- the greatest writer who ever lived -- rest in the hallowed ground of England's national church amongst the immortals of English letters" (Wright, "Who Was Edward de Vere?").