This page has been accessed

since 29 May 1996.

This page has been accessed

since 29 May 1996.

For further readings, I suggest going to the Media and Communications Studies website.

The toys smash into a wall and shatter in slow motion, body parts flying. The laughing little boys pick up the pieces, reassemble them, and throw the crash dummies in their little car against another wall to break again and again.

#

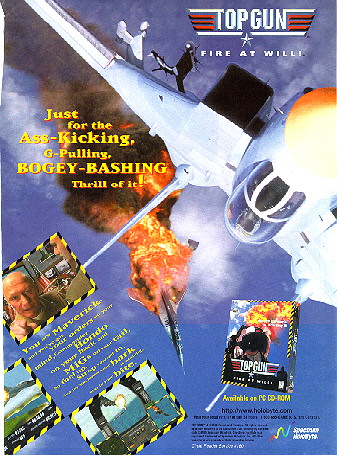

The plane searches the blackness, the pilot alert for enemy fighters. Suddenly,

out of the darkness, a swarm of enemy ships attacks! The brave pilot stares

intently at the TV screen and presses the fire button over and over, thrilling

to the explosions as he blows one enemy after another into oblivion.

The plane searches the blackness, the pilot alert for enemy fighters. Suddenly,

out of the darkness, a swarm of enemy ships attacks! The brave pilot stares

intently at the TV screen and presses the fire button over and over, thrilling

to the explosions as he blows one enemy after another into oblivion.

#

Sirens blare through the night, red and blue lights strobe in the darkness, in the distance a pillar of smoke lit up by fire and explosions fills the sky. As fire and police units near the scene of destruction, a voice says, "Would you get out in time? With a smoke alarm, you could."

#

The above are examples of the sixth appeal -- destructiveness. Destructiveness is the desire to destroy things. Although this desire is usually for a constructive end, it occasionally manifests itself in the sheer enjoyment of destruction.

Destruction has a bad reputation in today's world (and probably the past as well). This is because the reputation is based on social norms, not biological. However, destruction is a part of the functioning of any biological being, including humans.

The basic purpose of life is to reproduce itself. For any organism that wishes to survive long enough to reproduce, it must have a degree of aggressiveness. That is, it must force itself upon its environment, wrest from it what it needs to survive and reproduce. Destruction is one of its means of achieving these ends. This is particularly evident in self-preservation, sex and greed.

Self-Preservation

When an organism is presented with a dangerous situation, one that threatens its survival, it will often attempt to destroy the agent of that situation. For example, the body generates white blood cells and antibodies, the purpose of which is to destroy invading microbes. A mother gnu will attack and try to kill wild dogs attempting to prey on her young.

The above are examples of an organism protecting itself from physical attack. However, destructiveness is also a part of getting those resources that maintain, not just protect, life. These resources include food, drink, and shelter. Destruction is pa rticularly a part of eating. First, nothing can be eaten without destroying it. The function of eating is to break something else, be it plant or animal, into its component molecules and use those molecules to build and repair your own body.

Even plants destroy something in order to grow. They take in molecules such as CO2, H2O and NH3, break them down, use the elements they need to grow, such as carbon, hydrogen and nitrogen, and excrete the residue (mostly oxygen, which is how we breathe) . Granted, we don't think much of destroying molecules -- it's not in the same league as killing an elephant. Nonetheless, it is still destruction.

Sometimes the destruction isn't the primarily for the food; sometimes it simply happens as the animal tries to get the food. For example, elephants tear down trees to get at the leaves. That the tree is destroyed, not for food, but simply because it do esn't hand over its leaves willingly and insists upon breaking instead of bending, is beside the point. The tree is nonetheless destroyed.

Sex

In sexual animals, the male must often compete for breeding rights as part of his reproductive strategy (see Chapters 3 and 4 for a discussion of reproductive strategy). This competition often takes the form of ritualized or actual combat with other mal es. The combat requires one male to defeat other males, destroying them either psychologically or physically. The latter appears in ritual combat, when one male is able to demonstrate superior strength, aggressiveness, agility, or any other factor that convinces his opponent that actual combat would be futile. The opponent gives up.

The former, actual combat, appears when neither opponent convinces the other he is superior. In such cases, the opponents attack each other, biting, kicking, butting heads. However they fight, the purpose is to destroy the other's ability to continue t he fight, even to the point that one of the combatants dies. (Le Bouef, 1974)

Among some animals, it is the female who, as part of her reproductive strategy, is destructive. For example, the phalarope (a bird): in this species the female is promiscuous, mating with as many males as possible, laying her eggs in his nest (which he protects), then moving on to the next male. If the male has already mated and has eggs in his nest, she will destroy the existing eggs in order to mate with the male and use his nest. (Attenborough, 1992)

The cuckoo lays her eggs in other birds' nests, which the "foster" parent birds then care for. When the cuckoo chick hatches, its first action is shoving the original eggs or chicks out of the nest, thus monopolizing the foster parents' care. (Wallechin sky, 1993)

Thus, destruction is an instinctive element of reproduction.

Greed

Greed is the gathering of as many resources as possible in order to further one's own life or reproductive chances. This is not a problem when resources are abundant. However, if resources are scarce, competition arises. In such cases, organisms will fight for a larger share, driving out or destroying the competition.

As organisms become more complex, the gathering of resources takes on new dimensions. For example, chimpanzees organize into gangs to hunt, patrol their territories, and even fight wars to protect what they have and get more from others. If this sounds familiar, it is also what humans do.

Destructiveness is not only a biological drive; it is also a component of social life. It manifests itself in self-esteem, personal enjoyment, and constructiveness. However, destructiveness is socially unacceptable to many people since it is rarely a p ositive binding force, which is necessary to a viable society. It is true that a riot will unite a mob in a frenzy of destruction, but that can't be considered good for society at large. Thus, societies decry destructiveness as anti-social and that it s hould be eliminated. Nonetheless, no matter how much it is decried, it still exists to a greater or lesser degree in everyone.

One aspect that seems clear is that destructiveness is more attractive to males, especially young males, than to females. Males are more likely to attend monster truck rallies and demolition derbies, enjoy violent sports such as football, hockey and box ing, and act in a destructive manner.

That this begins at an early age is evident from the play activities of young boys. Unlike typical girls' play, boys' play covers more territory, includes setting relative status of participants, and involves more rough-and-tumble activity such as mock (or actual) fighting, wrestling, and verbal attacks. (Moir, 1991) These activities may be practice for future hierarchy battles that are part of the male reproductive and social strategies that appear throughout the animal kingdom.

As they get older, destructive activities decrease. The boys learn the nondestructive strategies that increase their chances at success in a culture that not only frowns on destruction as a means of being successful, but condemns those who are destructi ve to failure. However, it is clear that in subcultures in which destructive behavior is rewarded with status and/or wealth, destruction is still used. Such subcultures include many inner-city neighborhoods in which the normal, socially approved methods of succeeding that work only if nondestructive, such as jobs and education and economic opportunities, are minimal or missing entirely. In these subcultures, young males join gangs, sell and use drugs, commit acts of vandalism, and otherwise establish t heir standing in the hierarchy by being what the general society considers anti-social, but they consider normal behavior.

However, the majority of people do not live in these subcultures, and thus learn that destructiveness is the path to failure rather than success. Nonetheless, the appeal of destructiveness remains, particularly in terms of self-esteem, personal enjoymen t, and constructiveness, and particularly when aimed at males.

SELF-ESTEEM

Self-esteem requires comparing oneself to others. On occasion, some people find that they can raise their own self-esteem by destroying the self-esteem of those to whom they are comparing themselves. That is, they raise themselves comparatively by lowe ring others. This is particularly a male strategy, which depends on establishing a higher position in a hierarchy, rather than the female strategy of forming connections and bonds with others. In the former case, putting down someone else automatically raises a man's self-esteem in comparison to rher. In the latter, putting someone else down reduces a woman's self-esteem, since it weakens the bond she may have with that person.

PERSONAL ENJOYMENT

There are many beings that find enjoyment in destroying things. For example, as stated above, chimpanzees get together in gangs to go hunting. When they catch a monkey or small pig, they don't merely eat it; they seem to find great pleasure in tearing it apart alive. (Attenborough, 1992) Many children's toys, especially those designed for boys, are built around the idea of destroying things. This is particularly true of video games, in which the purpose is to destroy as many obstacles as possible.

Many people also find entertainment in destructiveness. Demolition derbies, rock concerts at which the performers break their equipment, football and hockey games, all have a strong destructive element. Some of the most popular recent movies, such as D ie Hard© and Terminator 2,© included destruction. And the bigger the destruction, the more excited the fans seem to get.

There seems to be a joy in destruction. People will get out of a warm bed in the middle of the night and stand for hours in freezing cold to watch a fire, the bigger the fire the better. People slow down when they drive past a traffic accident, rubbern ecking at the crumpled metal and broken glass, and hoping they don't (or maybe that they will) see blood and a body or two. Television news reports almost invariably contain shots of fires, accidents, riots, wars, hurricanes and other natural and human-m ade disasters. During the Persian Gulf War, ratings for news programs rose, and many people became news "junkies". The favorite parts of the coverage seemed to be for those that showed the "smart" bombs blowing things up.

CONSTRUCTIVENESS

Destruction is often a part of constructiveness, usually to make the constructiveness more appealing. It is destruction for a constructive end. Thus, we declare wars on drugs and poverty, "take a bite out of crime" , tear down slums, destroy disease, e tc.. All of the ends are constructive; the appeals are, at least in part, destructive.

Since destructiveness can be damaging to the social fabric, it rarely appears overtly in advertising since it could cause a backlash in the form of protest and negative publicity. However, since it is also a part of most people's subconscious motivation s, it can be effective in making a product or service seem more attractive. Thus, it will be used, but in subtle fashions.

Destructiveness is rarely used alone as an appeal. More often, it is linked with another appeal. Sex isn't used, but self-preservation, personal enjoyment, self-esteem and constructiveness are typical links.

A common use of destructiveness as an appeal is for products and activities

that are inherently destructive, and is usually linked with personal enjoyment.

For example, commercials for toys such as the Crash Dummies or video games

center on how much fun the players have fulfilling the toys' purpose --

destroying things. The fact that nothing is actually destroyed is irrelevant;

what's important is the feeling that using these products will allow you

demolish things.

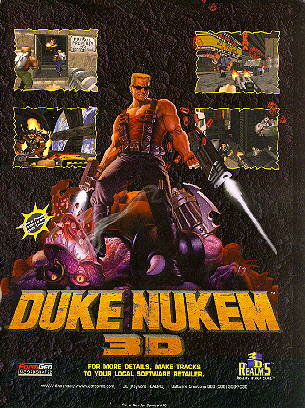

A common use of destructiveness as an appeal is for products and activities

that are inherently destructive, and is usually linked with personal enjoyment.

For example, commercials for toys such as the Crash Dummies or video games

center on how much fun the players have fulfilling the toys' purpose --

destroying things. The fact that nothing is actually destroyed is irrelevant;

what's important is the feeling that using these products will allow you

demolish things.

More often than products, services or events are promoted using destruction. Scenes promoting the enjoyment of sports such as football and hockey almost invariably center on violent actions such as fights, bone-crunching tackles and smashing bodies in g eneral.(1) Other events using destructiveness as the main appeal include monster truck rallies, demolition derbies and car races.

The most common types of ads that use destructiveness as an appeal are life-style and straight announcement, the latter using images of destruction around the announcement of the event or service.

Occasionally, destructiveness is linked with self-preservation. This approach, usually using the slice-of-life ad, is used for crime-fighting products, such as mace. For example, one ad shows a woman approaching her car in a dark garage. As the camera zooms in on her, she turns and sprays mace, leaving an impression that she has destroyed her attacker and saved her life. A more subtle use of destructiveness and self-preservation, using either the slice-of-life or testimonial types of ads, is for over -the-counter pain killers. As the product description implies, the product "kills" pain, destroying it.

More often, destructiveness is a subtle component in the appeals used in an ad, appearing more as an undercurrent than a direct statement. For example, occasionally ads will focus on self-esteem as a link with destruction, but they emphasis psychologica l rather than physical destruction. For example, an ad for business services or machines may show one man being more successful, because he uses the service or machine, than another with whom he is competing, destroying the self-esteem of the latter and boosting the self-esteem of the former.(2)

The most common type of ad using destructiveness linked to self-esteem is the slice-of-life (or slice-of-death), in which one character, using the product, is demonstrably more successful than his competitor.

Destructiveness is an inherent part of most organisms' make-up, providing as it does the instinct for and ability to compete successfully for the resources to survive and reproduce. However, it is also inherently selfish and anti-social for the same rea sons. Since humans are among the most social creatures on earth, destructiveness is unacceptable. Nonetheless, as a subconscious appeal, aimed at the instincts rather than the veneer of civilization society has laid over human instincts, it still has th e power to attract attention and add to a product or service's bundle of values for the consumer. This seems particularly true for males, from young boys to men.

Most often, destructiveness is linked to other appeals such as personal enjoyment and self-esteem. With personal enjoyment it is applied to toys and games aimed at boys, and sports aimed at men: it is an added element to the fun the toys or games can p rovide. With self-esteem, it is applied to the products or services that will provide the resources or edge a person needs to succeed in human society (see chapters 3 and 4 for a discussion of those resources).

(1) It is interesting to note that promotions

for non-violent sports such as baseball show feats of skill like home-runs

or incredible catches or well-executed plays. For violent sports, scenes

of skillful play are shown being successfu l despite the efforts of one

player trying to destroy the other, and it's the destruction, not the skill,

that is the focus of the scene.

Return

(2) Note that this scenario is rarely

played out using women as competitors, or showing the defeated competitor

being a woman. Women are generally more cooperative than competitive with

their coequals, so an ad showing the same cutthroa t competition that appears

in commercials with men wouldn't ring true. There are two possibilities

why men are not shown defeating women in business competitions. First,

it wouldn't be "gentlemanly;" that is, it would appear to many

that he was picking on her, which would reflect badly on the product or

service. Second, to many it would appear sexist, that he was able to defeat

her because he was male and she was female, not because he was using a

superior product or service, once again reflecting badl y on the sponsor.

Return

Return to Taking ADvantage Contents Page

Return to Taflinger's Home Page

You can reach me by e-mail at: richt@turbonet.com

This page was created by Richard F. Taflinger. Thus, all errors, bad

links, and even worse style are entirely his fault.

Copyright © 1996 Richard F. Taflinger.

This and all other pages created by and containing the original work of

Richard F. Taflinger are copyrighted, and are thus subject to fair use

policies, and may not be copied, in whole or in part, without express written

permission of the author richt@turbonet.com.

Disclaimers

The information provided on this and other pages by me, Richard F.

Taflinger (richt@turbonet.com),

is under my own personal responsibility and not that of Washington State

University or the Edward R. Murrow School o f Communication. Similarly,

any opinions expressed are my own and are in no way to be taken as those

of WSU or ERMSC.

In addition,

I, Richard F. Taflinger, accept no responsibility for WSU or ERMSC material

or policies. Statements issued on behalf of Washington State University

are in no way to be taken as reflecting my own opinions or those of any

other individual. Nor do I take r esponsibility for the contents of any

Web Pages listed here other than my own.

This Web page created in Web Factory.