SCENE i

|

Two gravediggers, serving the play as clown figures, discuss the issue of

Ophelia's burial in sacred Christian ground, even though her death

sounded accidental and not like suicide earlier. The two engage in

gallowshumor, which seems psychologically appropriate somehow. Hamlet and

Horatio overhear one of the gravediggers singing, and Hamlet remarks,

"Has this fellow no feeling of his business? 'a sings in grave-making"

(V.i.65-66). Horatio figures he's desensitized to it. Hamlet then

considers the bones and the common end to all politicians, lawyers, and

land-purchasers.

Hamlet enters into a chop-logic interchange with the gravedigger. ("Chop-logic" is dialectic banter in which confinement to particular meanings of words leads to ludicrousness -- think Abbott and Costello's "Who's on first.") After a humorous dig at England (V.i.149ff), Hamlet must now consider his idee fixe, death, not just in abstraction or brooding poetic indulgence, but in light of real personal connection. The scene is said to prove that Shakespeare knew the odd legal case of Hales v. Petet concerning suicide (Ogburn and Ogburn 646). |

|

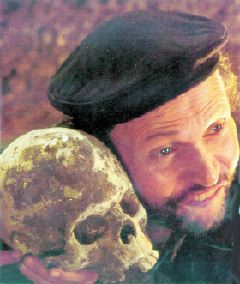

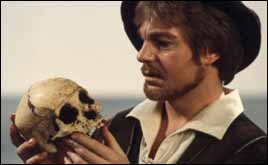

Handed the skull of the old king's jester, dead for 23 years now, Hamlet realizes: "Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio" (V.i.184). Hamlet's speech is a lot less self-indulgent now, as he considers the death that underlies all life, beauty, and human endeavor. And the stink also defies poetic indulgence (V.i.200). Note the overall development now of Hamlet's attitude about death, from the overwrought intellectualized ruminations about dissolving into dew, or "dreaming" after suicide in early acts of the play, then after killing Polonius indulging in the worms metaphor, to the gallowshumor with the gravedigger, to this final very real facing of death (so far as that is possible before one's own). There still may be an element of the fanciful here, but his understanding of literal death seems far more profound. "The skull of Yorick, the court jester during Hamlet's childhood, is in a way the antitype of the Ghost, material rather than spiritual" (Garber 503). Hamlet has matured: "by the fifth act, after the voyage to England, there are no more soliloquies. Hamlet now talks to others rather than to himself or to the audience, and his language is suddenly full of active verbs, verbs of 'doing'" (Garber 502). "Nothing of Hamlet's 'antic disposition' lingers after the graveyard scene, and even there the madness has evolved into an intense irony directed at the gross images of death" (Bloom 390). |

|

"Now get you to my lady's chamber, and tell her, let her paint an inch thick, to this favor she must come; make her laugh at that" (V.i.192-195). One may be put in mind of the heavily made-up Queen Elizabeth in the later years, and the ultimate impossibility of remaining a successful court jester (cp. Feste, Berowne).

All those court people attend Ophelia's funeral. Laertes is bombastic and given to excesses in behavior and rhetoric, including his jumping into his sister's grave. Hamlet presents himself and can be angry at Laertes now without losing his equilibrium, as his restrained and dismissive request shows: "I prithee take thy fingers from my throat" (V.i.260). He now has a toughness, but a humaneness. The tragedy is that he will never live to enjoy the fruits of this new self-knowledge. Hamlet is a bit confused regarding how rabid Laertes is, "But it is no matter. / ... / The cat will mew, and dog will have his day" (V.i.290-292).

What seems most universal about Hamlet is the quality and graciousness of his mourning. This initially centers upon the dead father and the fallen-away mother, but by Act V the center of grief is everywhere, and the circumference nowhere, or infinite" (Bloom 413).

SCENE ii

Note this perspective, something most of us don't apprehend until we're at the ends of our lives: "There's a divinity that shapes our ends, / Rough-hew them how we will" (V.ii.10-11). Hamlet explains to Horatio that he pulled a switcheroo with death letters so that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern will be killed in England instead of himself. In thus changing Claudius' "script," "He becomes what we could well call a ghostwriter, writing his anonymous script in the name of the Ghost, and for the revenge the Ghost has sought" (Garber 501). By Hamlet's reference to being able still to write "fair" despite trying to forget it (V.ii.34), "He means that he had once striven to forget the German or Gothic script still used for formal documents: that is to say, he wrote the Italian hand (as was the fashion with Elizabethan courtiers" (Ogburn and Ogburn 660).

Horatio provides a psychotherapeutic opportunity through Hamlet's self-disclosure with a trusted intimate, vs. male competitiveness. "This is the only time in the entire play that Hamlet openly admits that he had had 'hopes' for the succession and that it is a grievance to him that he was outmaneuvered in this respect by Claudius" (Asimov 143). Hamlet now regrets having "forgotten" himself -- his "tow'ring passion" (V.ii.80) levelled at Laertes. But he and Horatio have a laugh at Osric, a "busy trifler" of the court. In an exchange with him, Hamlet seems to show that Osric is the new Polonius (V.ii.92ff; cp. III.ii.376ff), just without the nasty skills yet. [Oxford must have someone specific in mind to pour this much attention into this superfluous character -- and to mention his position at court is based on the fact that "He hath much land" (V.ii.85); but it's much too late for it to have been Sidney, so who?] About the coming duel with Laertes, Hamlet seems resigned but not passive: "the readiness is all" (V.ii.222).

Before the duel, Hamlet asks Laertes' forgiveness, calling him "brother" (V.ii.244, 253), but Laertes is determined to see this through. [Regarding the sophisticated mathematical matter of the odds given in the betting on this duel, see Sam C. Saunders' "Could Shakespeare Have Calculated the Odds in Hamlet's Wager?" The Oxfordian 10 (2007): 20-34.]

Claudius poisons a stoup (tankard) of wine and tries to arrange for Hamlet to drink from it, but Gertrude accidentally does instead. Hamlet is wounded with the poisoned sword, but in turn, after a scuffle, wounds Laertes with it. Gert drops and dies blaming the drink. Laertes fesses and announces, "the King's to blame" (V.ii.320). So Hamlet wounds Claudius with the sword and forces him to drink the poison too. The King's last insistence is odd: "I am but hurt" (V.ii.324). Has tried all along to live as if life has no limits. It's an Elizabethan notion that one's death reveals one's true character: if you don't die with dignity, you must have led a life of self-betrayal. Thus, Claudius is in denial to the last.

So, in the heat of the moment finally, when all is unambiguously clear, including Claudius' evil, Hamlet can and does act. Besides, now it's personal and vicious against Hamlet -- no question here finally. "Hamlet has reached a state in which he can kill the King as by a reflex action; and now he is avenging not only his father's death but also his mother's and the act that is to bring about his own" (Wells 212).

Now remains Hamlet's death scene. The Prince refers intriguingly to matters that he has not discussed, but no time now.

I am dead, Horatio. Wretched queen, adieu!Horatio says he is "more an antique Roman than a Dane" (V.ii.341) -- meaning that his grief is turning into the suicide impulse. But Hamlet forbids it.

You that look pale, and tremble at this chance,

That are but mutes or audience to this act,

Had I but time--as this fell sergeant, Death,

Is strict in his arrest--O, I could tell you--

But let it be. Horatio, I am dead,

Thou livest. Report me and my cause aright

To the unsatisfied.

(V.ii.333-340)

O God, Horatio, what a wounded name,As Dr. Paul Altrocchi notes, "The Prince did not have a wounded name, nor was there any untold story within the play which was withheld from the world" ("Is a Powerful Authorship Smoking Gun Buried Within Westminster Abbey?" The Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter 44.3 (Summer 2009): 1, 3-13).

Things standing thus unknown, shall I leave behind me!

If thou didst ever hold me in thy heart,

Absent thee from felicity a while,

And in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain

To tell my story.

(V.ii.344-349).

Hamlet has the presence of mind to authorize Fortinbras as new head of state; "the rest is silence" (V.ii.358).

However, the injunction to 'tell my story' is also -- as we have seen so often at the close of Shakespearean tragedy -- an injunction to perform the play. In Romeo and Juliet, Othello, King Lear, Antony and Cleopatra, in almost every tragedy Shakespeare wrote, this invitation, to 'speak of these sad things,' is a way of making tragic events bearable, by retelling them, by placing them at once in the realm of the social and the aesthetic. (Garber 505)Hamlet's last words? Wrong. Check the First Folio. Hamlet ends with "O, o, o, o." All editors have just decided that since it sounds too awkwardly melodramatic in their imaginations, they should just leave out what the greatest writer ever to exist wanted the most important character he ever created to say with his last breath. (And check out Lear's ending too in the 1608 Quarto.)

Horatio's eulogy is poignant: "Now cracks a noble heart. Good night, sweet prince / And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest!" (V.ii.359-360). Hamlet had to find out who he was before undertaking the supreme task -- he needed self-knowledge. He matured, starting out bitter and morally arrogant, now able to die without self-pity. "Consciousness itself has aged him, the catastrophic consciousness of the spiritual disease of his world, which he has internalized, and which he does not wish to be called upon to remedy, if only because the true cause of his chageability is his drive toward freedom" (Bloom 430). Hamlet has avoided the traps of self-betrayal, unlike so many others here. "It outrages our sensibility that the Western hero of intellectual consciousness dies in this grossly inadequate context, yet it does not outrage Hamlet, who has lived through much too much already" (Bloom 429). The final party line is that the generations were too extreme and we needed a clean sweep to start fresh with Fortinbras who is solid, fair, and unthinking. But we sense the lost possibility and lost hope. Maybe one cannot live at Hamlet's pitch forever, but we still mourn the loss of it when it's gone. "It is we who are Horatio, and the world mostly has agreed to love Hamlet" (Bloom 421).

Fortinbras enters with ambassadors. Amid this bloodbath, the deaths of even Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are announced. Fortinbras sounds a little like Claudius: "For me, with sorrow I embrace my fortune" (V.ii.388). Horatio is left as the voice of the story; his voice and authority were considered valuable from the first (I.i.42). And he says this:

You from the Polack wars, and you from England,Is this all the Hamlet story? It sounds like a pyre of the collected plays in some respects. But even if so, how much is then real about the consequences? In other words, is Shakespeare talking about the play, or the plays, or the truth?!

Are here arrived, give order that these bodies

High on a stage to be placed to the view,

And let me speak to th' yet unknowing world

How these things came about. So shall you hear

Of carnal, bloody, and unnatural acts,

Of accidental judgments, casual slaughters,

Of deaths put on by cunning and forc'd cause,

And in this upshot, purposes mistook

Fall'n on th' inventor's heads: all this can I

Truly deliver.

(V.ii.376-386)

Fortinbras notes, "he was likely, had he been put on, / To have proved most royal" (V.ii.397-398). There's a final martial irony with the last word "shoot": "The sarcasm of fate could go no further. Hamlet, who aspired to nobler things, is treated at death as if he were the mere image of his father: a warrior" (Goddard, I 381).

No final explanation of Hamlet suffices, not even as nebulous autobiographical projection. The Cliffs Notes assertion of a Hamlet who is the victim of external circumstances, sentimental dreaming, debilitating melancholy, an Oedipal complex, and a ghost's misleadings, somehow still doesn't cut it. "Inwardnessas a mode of freedom is the mature Hamlet's finest endowment, despite his sufferings, and wit becomes another name for that inwardness and that freedom" (Bloom 401). "Hamlet is the perfected experiment, the demonstration that meaning gets started not by repetition nor by fortunate accident or error, but by a new transcendentalizing of the secular, an apotheosis that is also an annihilation of all the certainties of the cultural past" (Bloom 388-389).

Bloom appropriately quotes Nietzche's The Birth of Tragedy (1873), insisting that "Nietzsche memorably got Hamlet right, seeing him not as the man who thinks too much but rather as the man who thinks too well":

For the rapture of the Dionysian state with its annihilation of the ordinary bounds and limits of existence contains, while it lasts, a lethargic element in which all personal experiences of the past become immersed. This chasm of oblivion separates the worlds of everyday reality and of Dionysian reality. But as soon as this everyday reality re-enters consciousness, it is experienced as such, with nausea: an ascetic, will-negating mood is the fruit of these states.

In this sense the Dionysia man resembles Hamlet: both have once looked truly into the essence of things, they have gained knowledge, and nausea inhibits action; for their action could not change anything in the eternal nature of things; they feel it to be ridiculous or humiliating that they should be asked to set right a world that is out of joint. Knowledge kills action; action requires the veils of illusion: that is the doctrine of Hamlet, not that cheap wisdom of Jack the Dreamer who reflects too much and, as it were, from an excess of possibilities does not get around to action. Not reflection, no -- true knowledge, an insight into the horrible truth, outweighs any motive for action, both in Hamlet and in the Dionysian man. (qtd. in Bloom 393-394)

What would happen if someone like Hamlet actually had the chance to be a king? Interesting, no? Look at the jackasses who always are, and dream wistfully.

Biographical Notes

Oxford's favorite cousin was Horace (= Horatio) Vere, fifteen years younger. Oxford wanted to make him and his brother Francis Vere heirs to the earldom. They went on to become somewhat famous in the wars in the Low Countries as "the fighting Veres." Further, "given that de Vere grew up in a household with actors, a Hamlet-Yorick type of relationship ... would not have been out of the question" (Farina 197). Henry VIII's jester Will Somers, who died in 1560, has been suggested as the inspiration here (Clark 665; Ogburn and Ogburn 694; Anderson 190). Oxford's father, the 16th Earl, was Lord Great Chamberlain to Henry VIII from 1540 to Henry's death in 1547. From 1556 onwards, the 16th Earl was patron to his own troupe of players, so perhaps Somers did spend time at Hedingham (Clark 666).

In Hamlet's dying words, he asks that the true story be told. It's been hopefully speculated that perhaps Horace Vere was the man behind the Second Quarto edition of Hamlet published shortly after Oxford's death in 1604. Hamlet's final and invariably censored "O, o, o, o" may have served as de Vere's signature, the four Os being his court code number 40.

What Hamlet's succession might have meant may be seen by asking: What if, on the death of Elizabeth, not James of Scotland but William of Stratford had inherited the throne! That would have been England falling before William the Conqueror indeed. And it did so fall in the sense that, ever since, Shakespeare has been England's imaginative king, who has taught more men and women to play perhaps than any other man in the history of the world. (Goddard, I 386)Replace Stratford Will with the 17th Earl of Oxford, and it turns out not to have been such a wistful impossibility!