TWELFTH NIGHT,

The alternate title, "What You Will," translates fairly well into the modern idiom as "Whatever." This is fortunate because, lord knows, the notion of Twelfth Night seems to have little if anything to do with the play. Speculation has pointed to January 6th (the twelfth day of Christmas) indicating a "topsy-turvydom" of indulgent festivities (Wells 177), a revelry signifying the end of the holiday season. Even the subtitle "speaks both to this customary season of topsy-turvy revelry and to the space of fantasy and wish-fulfillment that was the early modern playhouse" (Garber 506). The play seems to designate an end of comedy or a farewell to wit of this sort in the artistic development of the playwright -- his efforts will focus on tragedies next (Goddard, I 295, 306). Or perhaps the play was designed for a particular occasion coinciding with Twelfth Night (Stratfordians say in 1601). Twelfth Night is also called the Epiphany -- and we may need one to grasp the underlying meaning in this play.

Although orthodoxy wants to insist that a key source for the play is Barnaby Riche's tale of "Apollonius and Silla" in Farewell to a Militarie Profession (Wells 182), they've got this backwards.

It so happens that Barnabe Riche is the last person Oxford would have derived anything from, even if he had had need of poaching and had not written his play at least a year earlier; for in this same book Riche had lampooned Oxford, at a time when the Earl's fortunes were very low; and besides, Christopher Hatton was Barnabe Riche's patron! Moreover, Riche stated on page 1 of his "Conclusion," that some of the stories he used had already "been applied to the purposes of the stage." (Ogburn and Ogburn 294)

|

In 1732, Francis Peck in Desiderata Curiosa noted plans to

publish "a pleasant conceit of Vere, Earl of Oxford, discontented

at the rising of a mean gentleman in the English Court, circa 1580"

(qtd. in Clark 364; Ogburn and Ogburn 267; Anderson 154; Farina 82),

and this is taken by Oxfordians to be a reference to an early now

lost version of Twelfth Night and part of Oxford's

rivalry with Sir Christopher Hatton. The actual main source is

Piccolomini's 16th-century commedia erudite from Siena,

Gl'Ingannati (The Deceived), involving brother/sister

twins (Anderson 102-103) and its prefatory story, Il Sacrificio,

featuring the character Agnol Malevolti (Ogburn and Ogburn 268), which

Oxford may have seen performed in Siena during Twelfth Night in 1576

with the "mock sacrificial homage to the spear-shaker goddess Minerva

that was an integral part of this entertainment" (Farina 83). Clear

evidence of later revision -- the elder Ogburns think in 1587 and

a bit again very late (Ogburn and Ogburn 266) -- includes the

shifting function of Viola at Orsino's estate, assignment of the

music, and the superfluous Fabian who seems largely eclipsed by Feste

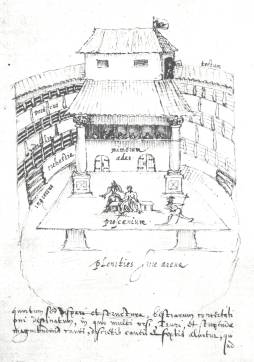

but not eradicated entirely. A sketch of The Swan theater in 1596 by

DeWitt may be depicting a scene from Twelfth Night, obviously

earlier than orthodoxy assumes the play was written (Clark 377-378).

The two ships named in the play -- the Tiger and the Phoenix

-- were "particularly active" about 1580 (Clark 379). King Sebastian of

Portugal died in 1578 and Antonio, natural son of John II of Portugal,

claimed the throne. Antonio received aid from England against Spain

(Clark 381). Spanish and Italian prisoners brought to England in

1579 included a Sebastian, an Antonio, and a couple Fabians (Clark

381).

|

|

I've seen an attempt to translate the subtitle "What You Will" into the French "Comme Tu Veux" -- sounding a bit like Comte (Count = Earl) de Ver. But I don't know about this one. The Winter's Tale is more convincing.

Perhaps Shakespeare pilfered from himself and his successes in the previous comedies for the combination of elements here (Goddard, I 294). But some other question (about identity? human interaction? the "will" of "What You Will"?) seems to be explored too in a new way. What would you say the world of Illyria represents? What is peculiar about the way everyone behaves, or runs their lives, in Illyria?

For a surprisingly insightful film-related web site on the 1996 Renaissance Films production of Twelfth Night, check out this.

ACT I

SCENE i

If music be the food of love, play on,Out of context, the first line sounds like a burst of romantic enthusiasm, but that's wrong. Orsino -- perhaps named for Don Virginio Orsino, Duke of Bracciano (northwest of Rome) who was a court visitor to Queen Elizabeth in 1600 (Asimov 576) -- claims to want to be so stuffed with music that he turns sick, so as to end desire by overdoing. (That's exactly why to this day I can't drink white wine.) He is "a willing prey to the fashionable Elizabethan affliction of melancholy" (Garber 509). Orsino is Duke (or Count) of Illyria -- formerly Yugoslavia (Asimov 575), now modern-day Dalmatia or Bosnia, but really just geographically vague for the purposes of the play. Still part of the Ottoman Empire in Shakespeare's day, parts of its coast "were controlled by Venice, and Italian in culture (Asimov 576). Orsino pouts and languishes, luxuriating in languid music and self-indulgently posing as a melancholic Petrarchan lover, ruled by his immediate sensory impressions; "he induces in audiences a sort of indulgent avuncularity" (Wells 178). But if his appetite for these indulgences were indeed to die, then what? Would he have any identity without this persona?

Give me excess of it; that surfeiting,

The appetite may sicken, and so die.

That strain again . . .

. . .

. . . Enough, no more,

'Tis not so sweet now as it was before.

(I.i.1-8)

Taking advantage of the hackneyed "hart"-hunting trope (I.i.16ff) and alluding obliquely to the Actaeon and Diana myth (I.i.21-22), Orsino claims to be pining for wealthy countess Olivia, who, we hear from a gentleman named Valentine, is too busy posing as a distraught mourner over her recently deceased brother. She plans to devote herself to grief for seven years now and cannot allow for a suitor. The imagery suggests that her teary eyes are either watering cans or pickling vats (I.i.29ff). All the better for Orsino's pining -- her withdrawal from public life shows how worthy she is, and his imagination is excited with her apparently devoted and romantic nature.

Orsino is "far more in love with language, music, love, and himself than he is with Olivia, or will be with Viola" (Bloom 229). "Orsino's initial passion, although he claims it is for Olivia, is rather for the spectacle of himself in love" (Garber 510). Worse than "in love with love itself," Orsino is obviously self-absorbed; still, this can be conveyed movingly "because his High Romanticism is so quixotic, but also because his sentimentalism is too universal to be rejected" (Bloom 230).

SCENE ii

Viola, and a Captain, and some sailors wash ashore; it looks as if Viola's twin brother Sebastian has drowned. The Captain supplies basic information about Illyria. "And what should I do in Illyria?" (I.ii.3), ponders Viola. She has heard of Orsino (even seems to know he likes music!) and either automatically thinks of him as a sexual target or secretly wants to avoid him (Sutherland and Watts 126). Olivia's situation of having recently lost her brother after her father's death some time ago resembles Viola's own.

The seemingly drastic plan for Viola to be presented as a eunuch at Orsino's court suggests sufficient danger in this alien land to warrant deep cover, but is there a real threat here? (The 1996 Renaissance Films version of this play creates it with nasty-looking posses patrolling the coastline.) Viola naturally, having lost a twin brother, may want to withdraw, and her disguise allows for this symbolically. Italian opera was the new Italian fad at the turn of the seventeenth century, and the Illyrian Ragusa developed its own opera outside of Italy (Anderson 87), so perhaps she thinks Orsino the music lover will welcome a eunuch -- typically recruited for this new art form. (So Shakespeare is probably acquainted with if not involved in opera during its early stage of evolution.) Her "boy's disguise operates not as a liberation but merely as a way of going underground in a difficult situation" (Barton, qtd. in Bloom 231). Viola is different from other cross-dressing heroines in that "she does not meet the man she loves until she is already in her gender disguise" (Garber 516).

Not simply just a mix of plots and subplots of the other comedies, Twelfth Night creates the sense "more of an integrated community" (Wells 180). But "Illyria is a counterfeit Elysium, a fool's paradise, where nearly everybody is drowned, drowned in pleasure.... Here there is pleasure and slavery to self" (Goddard, I 302). "And the people who come from the sea in this play seem to differ in temperament from the inhabitants of Illyria. They are active, while the Illyrians are passive. They are innovative, energetic, and daring" (Garber 508). "The theme of the main plot as well as that of the enveloping action, we suddenly see, is rescue from drowning: drowning in the sea, drowning in the sea of drunkenness and sentimentalism" (Goddard, I 305).

SCENE iii

Sir Toby speaks with Olivia's gentlewoman Maria on behalf of limitless self-indulgence, that is to say, partying. Olivia is reportedly dismayed by Toby's carousing. The wealthy Sir Andrew Aguecheek, whose foolish generosity Sir Toby enjoys, arrives and proves to be an idiot. "The name indicates his cheek has a habit of trembling, as though with ague or chills, but actually out of fear" (Asimov 578), or "suggests a cheek quiveringly inviting a slap or a challenge" (Ogburn and Ogburn 279). Although Andrew has studied languages, when he claims he'll ride home tomorrow and Toby asks, "Pourquoi," Sir Andrew is flustered: "What is 'pourquoi'? Do, or not do?" (I.iii.91) -- indicating that his automatic default assumption is that he is always being told what to do. "In a world of sheer revel, the word 'why,' the energy of motivation, has no meaning.... All of them lack the element of 'pourquoi'" (Garber 514-515). Andrew thinks himself a fascinating creature in the most vapid of observations: "I am a fellow o' the strangest mind i' th' world; I delight in masques and revels, sometimes altogether" (I.iii.112-114) -- in other words, I'm so interesting in this peculiar trait: that I enjoy fun. What a moron! But he hangs around due to Toby's promises that he would make a welcome suitor for his niece; "there is an uncomfortable economic basis to their relationship" (Wells 180). Toby commands Andrew to dance.

Sir Andrew also remarks, "I am a great eater of beef, and I believe that does harm to my wit" (I.iii.85-86). It's difficult to know what to make of this, but see Troilus and Cressida (II.i.13) and As You Like It (II.i.21ff and especially IV.ii).

It has been suggested that Andrew is a caricature of Sir Philip Sidney (Ogburn and Ogburn 275f; Anderson xxxii, 149; et al.) -- and Andrew is another version of Slender from Merry Wives (Ogburn and Ogburn 275; Bloom 237) -- and that Maria and Toby are Oxford's sister Mary de Vere and her husband Peregrine Bertie, Lord Willoughby -- the same two who inspired the characters Katherine and Petruchio in The Taming of the Shrew (Ogburn and Ogburn 199, 273-274; Anderson 131). Unfortunately, Toby is almost always cast as a Falstaff type instead.

|

The character Malvolio will prove the finest satire levelled at the pretentiousness of Sir Christopher Hatton, but a barb is included near the end of this scene too. About his dancing, Sir Andrew brags, "Faith, I can cut a caper" (I.iii.121). Sir Toby offers a culinary pun: "And I can cut the mutton to 't" (I.iii.122). Andrew quickly mentions his skill at "the back-trick" almost before we can detect an allusion to Hatton: her "Mutton" was Elizabeth's main nickname for him, along with "sheep" and "lyddes" (Clark 365). Then Sir Toby pontificates in mock-heroic tones: "Wherefore are these things hid? Wherefore have these gifts a curtain before 'em? ... Why dost thou not go to church in a galliard, and come home in a coranto? My very walk should be a jig. I would not so much as make water but in a sink-a-pace?" (I.iii.125-131). Hatton, ten years older than de Vere, gained Elizabeth's favor from his dancing and was sneeringly called at court "the dancing Chancellor" (Clark 364), so what a good way to mock any hyperbolic praise for him, the git! Hatton was "affected, self-righteous, deficient in the qualities of honor, generosity, finesse" (Ogburn and Ogburn 268). His rivalry with Oxford was intricate and ongoing, involving A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres (Clark 366f) and The English Ape, the Italian Imitation, the Footesteppes of France. He used the Latin poesy Fortunatus infoelix: the Fortunate Unhappy (Clark 367) -- significant in Act II here. The Italian source character Agnol Malevolti -- "near enough to a lamb, agneau, agnus, agnello" (Ogburn and Ogburn 268) -- makes even more sense of the Hatton identification, again given the "sheep" nickname. And the name Malvolio can also be construed from "Mal-vol-E.O.: evil-willer to E.O." (Ogburn and Ogburn 268). |

SCENE iv

The whole eunuch plan mysteriously disappears and Viola has been presented as a page named Cesario in Orsino's court. "Viola as a eunuch would not be fitted for the romantic role she is to have in the play, and the device of eunuch and mute is dropped at once and there is no mention of either at any later point in the play" (Asimov 577-578). Within only three days, the Duke has been much taken with this new young apparently male subordinate, and now enlists his help in tendering protestations of love to Olivia. Viola is doubtful about the likelihood of admission into Olivia's company, but Orsino is confident this will work. In discussing "Cesario's" voice for this enterprise, he notes, "thy small pipe / Is as the maiden's organ" (I.iv.32-33). Waa-ha-ha-ha-ha! Get it?

When he says, "for myself am best / When least in company" (I.iv.37-38), Orsino "is speaking in Oxford's person" (Ogburn and Ogburn 284) -- a realization expressed elsewhere (by Benvolio) and in a poem by de Vere: "That never am less idle, lo! than when I am alone" (qtd. in Ogburn and Ogburn 284).

SCENE v

Feste, whose name is close to the Italian word for "holiday" (Asimov 578), is Olivia's household "clown" or jester and has been truant from his job for a while. Maria warns him that Olivia may be angry at him for his absence. We don't know why Feste has been gone, but we come to perceive him as rather world-weary and disillusioned, or perhaps just burnt out as he has been in the employ of the household for more than a generation. "He carries his exhaustion with verve and wit, and always with the air of knowing all there is to know, not in a superior way but with a sweet melancholy" (Bloom 244). "Feste has the sadness that comes, we are told, of perfect knowledge" (Wells 184). Experience perhaps has damaged his capacity for joy. Feste is melancholy but without Orsino's self-indulgent sentimentalism. He is concerned with the moral welfare of those around him, as is shown here when he deftly proves Olivia a fool in an insightful and kindly interchange involving the folly of Olivia's mourning her brother when his soul is in Paradise (I.v.66-71). Feste sees through the artifice of Olivia's grief and would do his best to cure it. He may be the one character who is not a victim of his own imagination or misdirected passions. "He loves to sing, and his songs are all plaintive and in a minor key" (Goddard, I 301). Also though, "He is the artist at the heart of the play, the creator and entertainer who has constantly to strive to make contact with his audience, and who relies on his ability to do so for his very living" (Wells 184).

Feste is "deft" in addressing the issue of Olivia's grief (Garber 507). But here Malvolio, Olivia's steward, when asked by Olivia what he thinks of Feste, levels professional insults at Feste: "I marvel your ladyship takes delight in such a barren rascal. I saw him put down the other day with an ordinary fool that has no more brain than a stone. Look you now, he's out of his guard already. Unless you laugh and minister occasion to him, he is gagg'd" (I.v.83-88). Malvolio will pay dearly for this, later. It's easy to miss the importance of this moment, but Feste is touchy on this matter of his craft.

He is named Feste only once in the play, later, and calls Olivia "madonna," a title showing Italian influence (= "my lady"). She tells Malvolio, "O, you are sick of self-love, Malvolio.... There is no slander in an allow'd fool, though he do nothing but rail" (I.v.90-95). And this suggests that what we've got here is: 1) Olivia as Queen Elizabeth -- she even lapses into the royal "we" later in this scene (I.v.218) and the red and white Tudor colors are associated with her (I.v.239); 2) Feste as Oxford and his role as "allow'd fool" -- Elizabeth had to have liked and even encouraged these kinds of sometimes biting allegories as court entertainment (Anderson 57); and 3) Malvolio as Sir Christopher Hatton (further established later) with his aspirations to power and his animosity towards Oxford. "Oxford ... would never have dared to include the many personal allusions in his plays had not the Queen permitted, even encouraged, him to do it" (Clark 370; cf. Ogburn and Ogburn 503). Feste being the singer of songs in the play may parallel de Vere "hosting and entertaining" the French Duke of Alençon (one of Elizabeth's suitors) and company in September of 1579 (Anderson 149). And surely Oxford provided much more entertainment to the court than this, as is at least obliquely acknowledged in the contemporaneous record.

Maria announces that a young gentleman is at the gate. Olivia sends Malvolio to say that she's "sick, or not at home -- what you will" (I.v.108-109). "Her carefully announced, absurdly long period of mourning, with its withdrawal from society, is evidently a pretext, however unconscious, for singling herself out, making herself interesting" (Goddard, I 300). Sir Toby enters drunk, belching and blaming pickled-herring, also announcing the gentleman at the gate. When prompted by Olivia, Feste says that a drunken man is "Like a drown'd man, a fool, and a madman. / One draught above heat makes him a fool, the second mads him, and a third drowns him" (I.v.131-133). We have here an interestingly applicable scheme. Fools are funny, and appropriate for comedy. Madness can be humorous but tends to start seeming darker, as the madness theme in this play will prove. And drowning is mentioned in this play more than in any other except, appropriately, The Tempest (Goddard, I 305); several characters seem to be metaphorically drowning in Illyria, and this is much darker still in implications. We are invited to apply the scheme, as Feste declares Toby "but mad yet" (I.v.137). Some critics insist that madness runs rampant among the characters of the play: "everyone, except the reluctant jester, Feste, is essentially mad without knowing it" (Bloom 226). Others suggest that sickness is the more prominent theme. And sometimes Illyria is seen as a land of emotion. Certainly the characters seem mostly to be adrift.

|

Malvolio tells Olivia that the gentleman at the gate persistently insists on seeing her, "will you or no" (I.v.154) -- so it's not "what you will." She allows it, and ends up rather taken with "Cesario," the messenger of Orsino's declarations. The critical question is why? And what is Shakespeare saying about human attraction? Is it just that Viola (disguised as Cesario) is disturbingly blunt with her? That [s]he will not take no for an answer when it comes to calling on Olivia but gives "no" as an answer in the face of Olivia's come-ons? Cesario tells Olivia about her beautious qualities: Lady, you are the cruell'st she alive

|

|

This rhetoric is familiar from the Sonnets. Cesario reports what "he" would do if he loved Olivia as Orsino supposedly does, but Olivia repeatedly reasserts that she cannot love the Duke. When Cesario leaves, Olivia ruminates over his allusion to his social status: better than his present fortune. "'Cesario' has a powerful existence, eloquent, erotic, and elusive, that is not merely equivalent to the charms and power of the female character who portrays him" (Garber 517). Olivia senses her own attraction to the young "gentleman," and ends the scene with a ruse -- a ring she says Cesario left behind which must be returned with the message that he come again so she can explain her rejection of Orsino some more. "Olivia's passion is more a farcical exposure of the arbitrariness of sexual identity than it is a revelation that mature female passion essentially is lesbian," we are assured (Bloom 235).

Clark perceives the earlier version of the play as depicting Elizabeth as Olivia (cf. Anderson xxvii) and Alençon as Orsino. Viola represents "the latter's envoy and confidant, Count Jehan de Simier, then in England and 'making violent vicarious love to the Queen,' as Hume says" (Clark 367; cf. Ogburn and Ogburn 298). Indeed, the Elizabeth / Alençon relationship primarily amounted to lots of long-distance wooing through ambassadors in 1578 (Anderson 149). Besides various court personages, the Puritans were vocal against the Elizabeth / Alençon match (Clark 371). It has also been proposed that Viola functions as a composite of La Mole, the first envoy of Alençon in 1572, and Simier, the later one. Olivia's mourning is due to the St. Bartholomew massacre (Clark 376; Ogburn and Ogburn 281). The elder Ogburns, suspecting a 1587 revision of the play, suggest that Olivia partly represents Lady Mary Pembroke, mourning her brother Philip Sidney (Ogburn and Ogburn 281). The Sidneys' father had died a few months beforehand (Ogburn and Ogburn 282), a seemingly similar situation to Olivia's.