|

Chapter summaries

|

Online Chapter: Peace Symbols: Posters in Movements against the Wars in Vietnam and IraqNo Blood for OilWhile, given these complex constituencies, the amount and range of Iraq war posters is vast, many of the major themes of the antiwar/peace movement cluster in five areas: “weapons of mass deception” (i.e., war as reality TV or corporate ad campaign); the sexual politics of war; the clash of fundamentalisms; war as tied to domestic policy, clashes over patriotism, and American values; and, most ubiquitously, the politics of oil. As we will see, these themes are often woven together in a single poster. The Bush administration’s most often cited rationale for the war in Iraq was of course the claim that Saddam had developed “weapons of mass destruction.” Massive evidence now shows that to have been completely untrue, and much evidence suggests the administration knew it to be untrue from the beginning of the Iraq campaign. Both the selling of this pretext and attempts to distract from it when its falseness became clear have been a major focus of antiwar posters. In addition to the parody movie poster genre cited above (Figure 109), virtually all other forms of popular culture, from video games to television news, have been challenged for their complicity in selling the war. Figure 27, for example, ties the war to the pervasive computer and video war games that not only desensitize us to killing but are even being used now by military recruiters to ease the transition between war games and the “game” of war.13 “These Are Not Special Effects” (Figure 28) comes at this dynamic from another direction, underscoring the way in which the media reinforces the unreality of war through its dramatic “coverage” —a word that inadvertently suggests that the truth is covered up more than it is revealed by TV “news.”

Figure 27. “This Is Not a Game,” Dara Gill, circa 2003. Courtesy of Miniature Gigantic. Another pervasive dimension of popular culture, advertising, has also been much parodied by antiwar posters. The themes are usually of one of two types: the war as “sponsored” by corporations with a profit motive (Figure 29), including but beyond oil (the Middle East is a largely untapped market region for U.S. multinationals), or commercialism as a ubiquitous distraction from the realities of war (Figure 30). The poster “Freedom Fries” both lampoons the petty attempt to boycott all things French because France opposed the U.S. intervention, and suggests that the arms industry has become as normalized as the fast food industry and as widespread as McDonald’s franchises. Indeed, in many of the wars around the world, including Iraq, all sides are fighting with weapons originating in the United States.

Figure 29. “Logo Tank,” n.d. Courtesy of Cyberhumanisme. The sexual politics of the war have been approached in a number of different ways, but perhaps most commonly in the mode of a “boys and their toys” critique of the masculinism that finds war more manly than diplomacy, drawn largely from the long history of feminist antimilitarism. A number of posters have taken this logic a step further, by finding a homoerotic subtext in the male bonding around the war. Another variation on the “Make Love Not War” theme (Figure 31) suggests that the political strange bedfellows, conservative George Bush and liberal Tony Blair, might get the erotic thrill of their manly mutual pursuits by a more direct means.

Figure 31. N.d. Courtesy of Le doigt. Issues of religious fundamentalism and gender politics have also been tied together in posters. An argument honed in the Afghanistan campaign and transferred to Iraq was the notion that the United States was fighting to save Middle Eastern women from oppressive religious traditions like the wearing of veils and the burka. Not lost on U.S. activists was the irony of an antifeminist promoter of Christian religious patriarchy defending Afghan and Iraqi women. Less obvious, perhaps, was the fact that actually existing feminist groups within Afghanistan and Iraq condemned the U.S. presence there and had a very different notion of how to liberate the women of those countries, one that included recognition that veils, burkas, and other religious attire had many different meanings in differing contexts. The women of RAWA (Revolutionary Association of Women of Afghanistan), for example, the main feminist organization in country since 1977, fought the Taliban for years before the U.S. intervened, and now fight the U.S.-imposed regime of Hamid Karzai. They have criticized the religious intolerance and hypocrisy of the military occupation while maintaining their own secular version of women’s rights and full democracy. The racist assumption that all Arabs are alike also veils the fact that under Saddam’s hideous but secular regime women were not required to wear religious attire and that Iraq has a long history of highly educated and professionally active women. The poster in Figure 32 offers a complex set of comments on this pretext of fighting Islamic fundamentalism that was another of the many, shifting rationales for going to war.

Figure 32. “Free Market Fundamentalism,” Leon Kuhn, 2003. Courtesy of Leon Kuhn. In addition to mocking G. W. Bush’s concern for Middle Eastern women, this poster juxtaposes the supposed problem with its proposed military solution, and unveils that solution as bringing not “freedom” but the free market to Iraq and the U.S. corporations who would benefit from that limited version of freedom. Domestic U.S. politics and a struggle over “American values” figure into the war poster in a number of different ways beyond the question of corporate profits. Perhaps most common are attacks on U.S. freedoms rationalized as part of the war on terror, and a parallel claim that to question these limitations on freedom in the United States is to be unpatriotic. In “Democracy Threat” (Figure 33), this takes the form of at once parodying the color-coded terrorist threat system, which many activists see as a means to frighten the U.S. populace into embracing Bush, and the ironic threat to U.S. democracy posed by the crusade to “bring democracy” to the Middle East. “Got Democracy?” (Figure 34) takes this issue on more directly through another key word much used in Iraq, “democracy”; how, it asks, is torturing Iraqis going to endear people to promote a U.S. version of democracy? “The American Way” (Figure 35) uses six simple words and a crayon to make a parallel argument that American values have been reduced to American military power.

Figure 33. “Democracy Threat,” Fact Shirt, n.d. Courtesy of Fact Shirt.com. “Skate Poster” (Figure 36) is a uniquely self-referring poster showing young skateboarders looking at an antiwar poster. The poster depicts police brutalizing a protester, rather than a scene from the war, and includes in some versions text from the antiglobalization movement linking peace to questions of justice. It also seems to play on youthful bravado in the face of authority to challenge the dominant war story told by the White House.

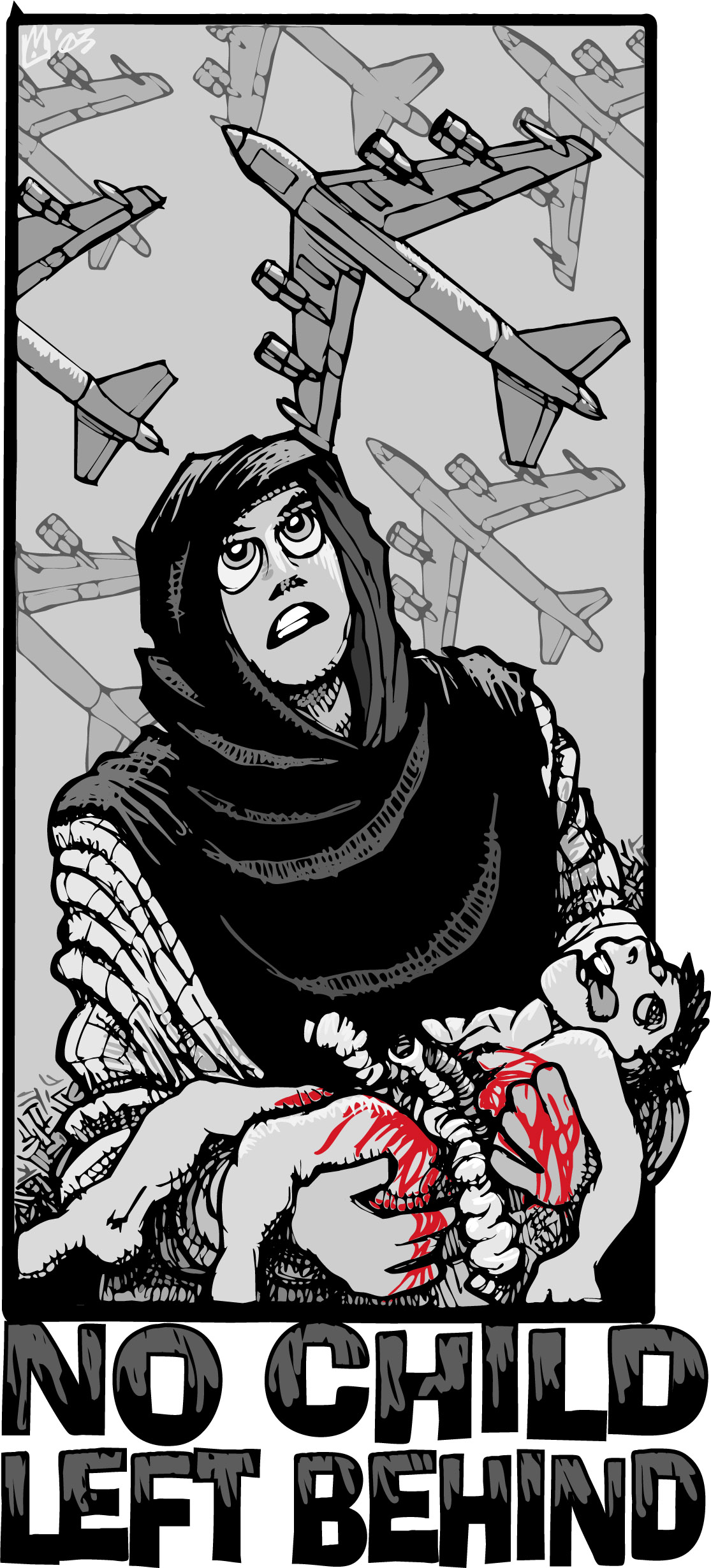

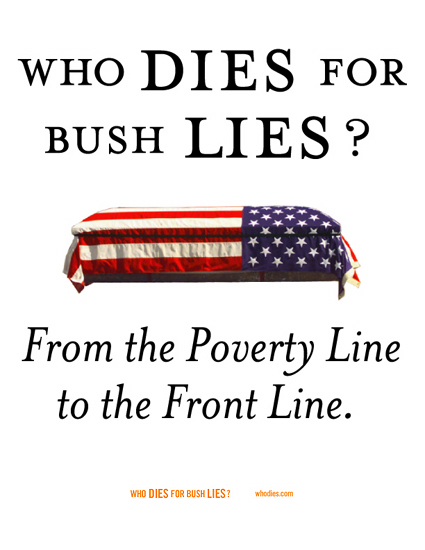

Figure 36. “Skate Poster,” Jai Redman, n.d. Courtesy of UHC Collective. “No Child Left Behind” (Figure 37) approaches domestic policy in a different way. It shifts the meaning of Bush’s famous slogan about school curricula and offers a subtext pitting declining funding for education in the United States to the costs, both human and financial, of the war. “From the Poverty Line to the Front Line” (Figure 38) attacks this issue from a different angle by referencing what some call the “poverty draft”—the fact that our volunteer military is often the only job option for poor and low-income folks in the society.

Figure 37. “No Child Left Behind,” Mike Flugennock, n.d. Courtesy of Mike Flugennock. Figure 38. “From the Poverty Line to the Front Line,” Committee to Help Unsell the War, 2003. Courtesy of the Committee to Help Unsell the War. No doubt the most famous slogan emerging out of the two U.S. wars in the Persian Gulf has been “No Blood for Oil.” The slogan in fact was born during the first Persian Gulf War but much more effectively recycled during the war in and occupation of Iraq. While the slogan is strikingly straightforward and seems simplistic, it can encapsulate a very complex analysis, as the many different ways in which the slogan has been incorporated into posters reveals. The much-repeated slogan takes on very different nuances depending both on the national or local context in which it is used and on the larger symbolic context of particular posters.14 Its obvious reference to the vast oil reserves in Iraq, for example, is augmented in many posters with words and images arguing that Iraq is not just only a site for oil exploitation but also a strategic space from which the United States hopes to control the flow not just of oil but of political influence over the entire Middle East: oil not just to power our vehicles but and to power politics. However, the relation to the huge consumption of petroleum in the United States is hardly ignored. Another of Micah Wright’s remixed recruitment posters (Figure 39), for example, asks, “Is your SUV worth it?” And the other side of the battle line is evoked, along with the question of so-called collateral damage (killing innocent civilians), through this image of an Iraqi boy with the gas nozzle held to his head like a gun (Figure 40).

Figure 39. Micah Wright. Courtesy of the Propaganda Remix Project. Another blood for oil poster (Figure 41), offers a rich yet simple image that ties together themes of profiteering, media unreality, and the human costs of war: a gas pump that looks a lot like a television screen, a nozzle transformed into a gun, and a blood red message (fill her up) that links sexual violence to war.

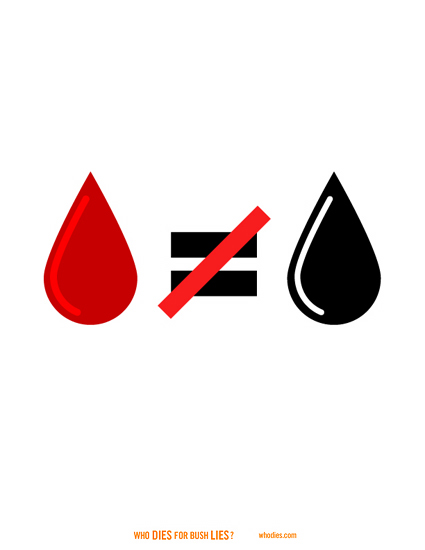

Figure 41. Michael Redding. Courtesy of Miniature Gigantic. Eventually the best-known slogan becomes so well-known that it can be pared down to stark, wordless eloquence that continues to speak in the face of ongoing violence and deception and for continued efforts to bring peace through justice to the Middle East (Figure 42).

Figure 42. The Committee to Help Unsell the War, n.d. Courtesy of Who Dies. 13 See, for example, the Army’s popular game America’s Army: The Official Video Game of the U.S. Army. 14 Much of my analysis in this section has been made possible by the rich collection of posters on the Iraq war, Peace Signs: The Anti-war Movement Illustrated, ed. James Mann (Zurich: Edition Olms, 2004). My chapter title is also inspired by (or stolen from?) their book title. |

|||