I'm relying on my own

interpretations of Homer's Iliad and Eastwood's

Unforgiven here and doing what Harold Bloom (on a good day)

refers to as "the necessity of misreading." No one "can evade a

Nietzschean will to power over a text, for interpretation is at

last nothing else."

The duality of Achilles is visible in two Academy Award winning

films. First I give a brief nod to Francis Ford Coppola's

TheGodfather. The story of Michael Corleone, the youngest

and most innocent member of the Corleone crime family, is the

story of the "Best"

becoming the "Beast":but

the similarities between Achilles and Michael Corleone are

somewhat tricky to enforce across two plus millieniums. The film

finds deeper roots in the Roman story of devotion to a higher

authority, an authority that is capable of incredible brutality.

The scupture of the Etruscan

wolf,

for instance, is said to represent the duality of Rome, but this

image could just as easily represent the Godfather as portrayed in

Coppola's film.

In Unforgiven, Clint Eastwood uses the western genre to dramatize the frightening power of wrath. Eastwood's character William Munny is a contemporary cowboy Achilles. In an interview with Terry Gross on "Fresh Air," Clint Eastwood said that he was, in Unforgiven, myth-making, deromantizing violence and gunplay. His character,William Munny, is a man aware of his part in the mayhem and violence of the past, yet he continues to follow through with the killing. In both the Iliad and Unforgiven violence has little or nothing to do with morality, with the undoing of evil, for their are no definitive representations of good guys and bad guys.

One could argue that the Iliad is both propaganda for and against war (although John Garder denounces a reading of the Iliad as antiwar). Homer romanticizes/ glorifies violence yet shows us the enormous human costs of such heroic endeavors. Achilles knows up front that continued fighting will also bring his own death (his horse tells him as much), yet he fights on with a horrific veracity.

Some scholars suggest that the Iliad (in one of its earlier oral forms) ended with the death of Hector. Such a narrative leaves out the supplication of Priam and the return of Achilles to a renewed sense of humanity. Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven ends in such a way. William Munny unleashes his overpowering wrath on the town's lawmen because they killed his friend Ned. The sheriff, Little Bill, resembles a kind of womanless Hector; he defends the town and is building a house and therein his violent encounters with other warrior/gunmen is related to and dependent on domestic life, just as the warrior's actions in the Iliad acquire validity in agrarian imagery and similes. Ned is a kind of western Patroclus--he is gentle, and we get a sense that he is caught up in the camaraderie of the expedition with Munny, but the killing for booty goes against his true nature. In the end, William Munny becomes the personification of unlimited carnage, the archetype of wrath--the beast. "I've killed women and children and everything that has ever walked or crawled." We even have the poet-journalist present to record the deed into Western mythology. And of course the whole quest and quarrel is taking place because of a woman. And it seems that the last bloody showdown inside the saloon opens with a thunder clap from Zeus.

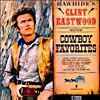

One

of the things that makes Eastwood's film so worthy of award is the

duality of William Munny himself, for like Achilles he is "the

great and terrible man." What I find amusing is the accumulative

effect of Eastwood's career on my reading of Unforgiven as

Iliad-like. Clint Eastwood, like Achilles, is a singer of

songs--remember the LP "Clint Eastwood sings Cowboy Favorites"?

Probably not. These straight songs were a spin-off of the TV

series "Rawhide." Eastwood has become an Achilles-like archetype

defined in part by the motif of the singing cowboy capable of

violence in the service of justice or just for the pure Hell of

it. The iconography

of his face

represents the depths of that violence. William Munny, as a

complex character, enters the same depths of sorrow that Achilles

enters. Like Homer, Eastwood glorifies the brutal killing as

tragedy. The hero's wrath leads to the questioning of his humanity

and our own as homo sapiens.

One

of the things that makes Eastwood's film so worthy of award is the

duality of William Munny himself, for like Achilles he is "the

great and terrible man." What I find amusing is the accumulative

effect of Eastwood's career on my reading of Unforgiven as

Iliad-like. Clint Eastwood, like Achilles, is a singer of

songs--remember the LP "Clint Eastwood sings Cowboy Favorites"?

Probably not. These straight songs were a spin-off of the TV

series "Rawhide." Eastwood has become an Achilles-like archetype

defined in part by the motif of the singing cowboy capable of

violence in the service of justice or just for the pure Hell of

it. The iconography

of his face

represents the depths of that violence. William Munny, as a

complex character, enters the same depths of sorrow that Achilles

enters. Like Homer, Eastwood glorifies the brutal killing as

tragedy. The hero's wrath leads to the questioning of his humanity

and our own as homo sapiens.