An Overview of Advertising

by

Richard F. Taflinger

This

page has been accessed since

28 May 1996.

For further readings, I suggest going to the Media and Communications Studies website.

This Chapter is a basic overview of advertising. Included is a history, a definition with an in-depth discussion and some comments on regulation.

- General Discussion of Advertising

- A Definition of

Advertising

The famous actor hugs the little girl in the wheelchair, looks out at the audience with dewy eyes, and says, "Give so more may live."

#

The car rapidly approaches a brick wall and slams into it head-on. At that instant, an air bag bursts from the center of the steering wheel, stopping the driver from ramming into the windshield. The bag deflates and the uninjured driver steps out of the wrecked car.

#

A man enters a crowded bar and orders a drink while talking on his cellular phone. He offers the three lovely women next to him a drink. At that moment his phone rings: it's a call from three men farther down the bar who ask to talk to the three women. They offer the women a certain brand of beer, and the women immediately accept, leaving the first man alone with his phone.

#

Since this is an advertising book, I'm sure you all recognize the above as examples of ads. What may not be clear is what is happening beneath the surface of those ads to make them particularly effective.

What each of the ads does is not aim at a consumer's intellect in order to sell the product. Instead the aim is at the consumer's psyche, the consumer's subconscious mind and emotions.

How they do that is the purpose of this book.

#

Before examining how advertising appeals to your psyche, it's a good idea to review some basic principles of advertising. These include its purpose: to identify products and differentiate them from other products. After all, if you haven't identified a product and shown how it is different from other products, why should anyone bother choosing your product over someone else's? That's a good way to lose money.

However, let's start at the top. Advertising is a major tool in the marketing of products, services and ideas. The idea is to sell them to consumers. Companies certainly think it's a good method of selling, and have increased their advertising year after year. In 1985, the March 28 issue of Advertising Age magazine listed how much the top ten advertising agencies billed companies worldwide for advertising in 1983 and 1984. In 1983, $19,837,800,000; in 1984, $23,429,700,000. The March 25, 1991 issue of Advertising Age listed a total of almost $52 billion for 1990. That's a 260% increase in seven years. Clearly, companies believe in advertising.

It's not a new idea.

Advertising has been around for thousands of years. One way of looking at the

cave paintings of

Nonetheless, advertising recognizable as advertising has been around for millennia. Daniel Mannix, in his book on the Roman games, Those About to Die, quotes an ad found on a tombstone:

"Weather

permitting, 30 pairs of gladiators, furnished by A. Clodius Flaccus, together

with substitutes in case any get killed too quickly, will fight May 1st, 2nd

and 3rd at the Circus Maximus. The fights will be followed by a big wild beast

hunt. The famous gladiator Paris will fight. Hurrah for

For the first few thousand years, people used advertising to promote two things: locations and services. The above is an example of the first. So were the signs outside taverns and inns.

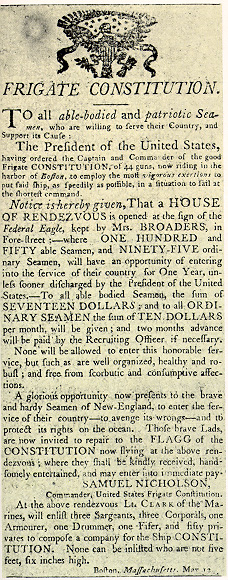

Handbills and

posters were also a popular form of advertising. They were passed out promoting

such events as plays, or recruiting for the military. For example, in 1798 the

captain of the

"

To all able-bodied and patriotic Seamen, who are willing to serve their

Country, and Support its Cause:

"

To all able-bodied and patriotic Seamen, who are willing to serve their

Country, and Support its Cause:

"The President

of the

"Notice is hereby given, That a HOUSE OF RENDEZVOUS is opened at the sign of the Federal Eagle, kept by Mrs. BROADERS, in Fore-street;--where ONE HUNDRED and FIFTY able Seamen, and NINETY-FIVE ordinary Seamen, will have an opportunity of entering into the service of their country for One Year, unless sooner discharged by the President of the United States.--To all able bodied Seamen, the sum of SEVENTEEN DOLLARS; and to all ORDINARY SEAMEN the sum of TEN DOLLARS per month, will be given; and two month s advance will be paid by the Recruiting Officer, if necessary.

"None will be allowed to enter this honorable service, but such as are well organized, healthy and robust; and free from scorbutic and consumptive affections.

"A glorious opportunity now presents to the brave and hardy Seamen of New England, to enter the service of their country--to avenge its wrongs--and to protect its rights on the ocean.

Those brave Lads, are now invited to repair to the FLAGG of the CONSTITUTION now flying at the above rendezvous; where they shall be kindly received, handsomely entertained, and may enter into immediate pay." (Gruppe, p. 27)

Other kinds of signs, hanging outside shops, promoted services. For example, bootmakers would hang a boot shaped sign outside their shops to let consumers know where to go to get their footwear. However, this was not product advertising so much as service advertising. Yes, the product was boots. But the sign was to tell people where they could get boots made. The bootmaker didn't have a large stock of merchandise that the consumer could buy on the spot. Instead, he had samples of his work. The customer would choose what rhe wanted, the cobbler would take measurements, make the footwear, and the customer would come back later to get it.

In both cases, what was being advertised wasn't products. The purpose of the advertising was to gather people, as audience, as recruits, as customers.

It wasn't until the Industrial Revolution at the beginning of the 19th Century that true product advertising began. This was because, for the first time, products were being mass produced rather than to order. This led to three eras in marketing.

The first era was production-oriented. When mass production began, it was still limited. Demand exceeded supply. There was no need to promote products when they sold as soon as they were made.

However, as time went on, production expanded and created a surplus of goods. Supply exceeded demand. This led to the sales-oriented era. Companies would promote their products to convince consumers to buy their products rather than their competitors'. Nonetheless, manufacturers still produced what they wanted to, counting on their ability to peddle their products.

Eventually, though, the supply so far exceeded the demand that consumers had more choices than any promotion could overcome. In addition, they developed a resistance to "hard-sell" advertising. Producers began to realize that it made more sense to find out what the consumers wanted before making them, rather than trying to talk them into buying afterward. We are, to a large extent, in this marketing-oriented era today.

An example of this progression is the American auto industry. When Henry Ford invented the production-line method of manufacturing cars, there was no need to promote them -- cars were sold before they were built. This was production-oriented marketing of cars.

As time went on, more manufacturers started building cars, and the supply of cars went up. Advertising likewise went up, as producers tried to convince consumers that their car was better than a competitor's car. Nonetheless, the manufacturers made their cars as they wished. They counted on the advertising to convince people that whatever feature they put in the car was what people want, whether it was two-tone paint jobs, three tons of chrome, or fins like the tail on a 747.

However, when non-American manufacturers entered the American market, they first tried to find out what Americans wanted in their cars. The first and greatest example is the Volkswagen bug. American cars were big, long, wide, flashy, gas-guzzling, and changed in appearance every year. The bug was small, ugly, and gas-efficient. It was also easy to park, cheap to run, ran forever, and never changed appearance just to go out of style. What changed was what consumers said they wanted (like a gas gauge!). As other non-American manufacturers entered the market, they also found out what consumers wanted, then built their cars that way. This was marketing orientation.

Of course, marketing orientation doesn't mean "no advertising." Advertising is just as important in marketing orientation as in sales. It's the approach that changes.

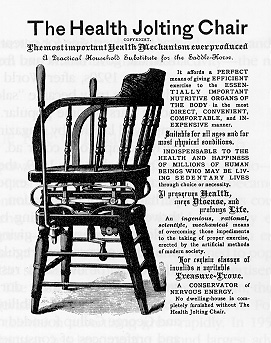

Early consumer advertising during the sales-oriented era was basically caveat emptor ("Let the buyer beware"). Producers said just about anything they wanted in their ads. For example, a product of the 1880s was the "Health Jolting Chair," a chair festooned with springs and levers. The copy extolled its virtues to the skies:

"The

most important Health Mechanism ever produced . . .

"The

most important Health Mechanism ever produced . . .

"It affords a PERFECT means of giving EFFICIENT exercise to the ESSENTIALLY IMPORTANT NUTRITIVE ORGANS OF THE BODY in the most DIRECT, CONVENIENT, COMFORTABLE, and INEXPENSIVE manner.

"Suitable for all ages and for most physical conditions.

"INDISPENSABLE TO THE HEALTH AND HAPPINESS OF MILLIONS OF HUMAN BEINGS WHO MAY BE LIVING SEDENTARY LIVES through choice or necessity.

"It preserves Health, turns Disease, and prolongs Life.

"An ingenious, rational, scientific, mechanical means of overcoming those impediments

to the taking of proper exercise, erected by the artificial methods of modern society.

"For certain classes of invalids a veritable Treasure-Trove.

"A CONSERVATOR of NERVOUS ENERGY.

"No dwelling-house is completely furnished without The Health Jolting Chair." (Bovee, p. 19)

Quite a chair, wasn't it? Actually, it wasn't, and such extravagant claims, especially for patent medicines and health devices led to consumer anger. It also led to legislation that required advertisers to substantiate their claims. In 1938, the Federal Trade Commission was given the power to protect consumers and competitors from deceptive and unfair advertising. Since then, advertising has gone through several schools of thought. In the 1940s and 50s ads stressed the upward mobility provided by products. It was also the era of Rosser Reeves' irritation school of advertising, a hard-sell approach. Ads, particularly television commercials, relied on brain-numbing repetition and treated the consumer as an idiot. The basis of Reeves' approach was the Unique Selling Proposition -- the USP. The USP was one unique feature of the product that was emphasized in the ad. Reeves believed that the consumer couldn't handle more than one point at a time, and limited each ad to one point, repeated over and over.

However, the 1960s shifted into a new approach -- positioning. Instead of promoting a USP, advertising showed how a product compared with other products, where the product fit into the market. The most famous example of this was Doyle, Dane, Bernbach's Volkswagen campaign. In ads that used headlines such as "Think Small" and "Lemon", Volkswagen was positioned in the auto market as an intelligent alternative for intelligent people.

This was the beginning of the soft-sell approach. Soft-sell depends less on product description or function, and more on how the product will make the consumer feel emotionally. It is in this approach that the psychological appeals become important, since they aim at a person's emotions rather than rher intellect.

#

How advertising goes about carrying out the above is many and varied. What follows is a discussion of many of the types and styles of ads that are used.

Before doing that, however, some general comments about ads that are germane to the purpose of this book. First, advertising is limited in both time and space. Broadcast commercials are generally 10 to 60 seconds in length. Print ads are generally no larger than two pages, and often much smaller. Advertising therefore must do its job quickly: it must get the consumer's attention, identify itself as being aimed at that consumer, identify the product, and deliver the selling message, all within that small time or space. To accomplish this, advertising often breaks the rules of grammar, syntax, image, and even society. For example, it relies on stereotypes to help the consumer identify the target market and the product (I discuss this point in more depth in Consumer Psychology).

#

Second, advertisements generally contain two elements: copy and illustrations. Copy is the words, either printed or spoken, that deliver a sales message. Illustrations are the pictures, either drawn or painted, or photographs.

A point to bear in mind about copy and illustrations is the difference between intellectual and emotional processing of information in the human mind. Copy relies on intellectual processing. It has to, since converting the squiggles on a page (which is, after all, what printing is) or the random noises issuing from someone's mouth (which is, after all, what speaking is) must be translated into meaning in the reader's or listener's mind. Just think about reading or hearing a language you don't know: for you, it's just so much waste of ink or noise as far as content is concerned. Such a translation is an intellectual process. Words, particularly if spoken, can carry great emotion--they can create images before the mind's eye or call up events that can make you laugh or cry. Spoken words have the advantage over printed words of extra nuances, such as inflection, rate, volume, and timbre that help the listener translate the noises into meaning. Nonetheless, words are always one step away, the step of translation, from "reality."

Although at first glance it may not seem so, drawings and paintings also rely on intellectual processing. Drawings and paintings, like words, are not the things themselves, but an artist's conception of them. The lines, shapes and colors must be translated into meaning in the mind of the viewer. Again, illustrations can carry great emotional impact, particularly paintings with their greater verisimilitude, but also again they are one step away from "reality."

Photographs, either still or moving, rely on emotional processing. To the mind, they are the thing itself, and therefore need no translating to determine what they mean. Of course, any photograph is, like a drawing or painting, the product of an artist's conception. Rhe selects, frames, composes, determines exposure, angle, distances, depth, etc., to present whatever emotional message rhe desires. Nonetheless, a photograph has an immediate impact on the viewer, with no intervening step between perception and reaction.

Most ads contain a combination of copy and illustration, in proportions ranging from all one to all the other, depending on the how the advertiser wants to present rher sales message.

There are two basic ways of presenting a sales message: intellectually and emotionally. An intellectual presentation depends on logical, rational argument to convince a consumer to buy the product or service. For example, for many computer purchasers, buying doesn't depend on what the case looks like or what effect the machine might have on their social life. What they're looking for is technical information: how fast does it process information, how much RAM, how big and fast is the hard disk drive, how many and what type of floppy drives, how big is the power supply, what is the resolution of the monitor? Other products that are sold more for their functions than other possible aspects in the consumer's "bundle of values" include some business and financial services, computer programs and accessories, construction materials and tools, and other complex but less than "romantic" products.

Such ads are "copy heavy," since the sheer amount of information to explain the functions and benefits of the product or service requires many words. In addition, such ads usually appear in print media since it takes time and concentration on the consumer's part to absorb and understand the information. Such time and concentration characteristics are lacking in broadcast media.

Illustrations are often sparse in intellectually aimed ads, and those will usually be drawings or paintings, thus keeping both elements aimed the same way. If photographs are used, they will usually be stark and simple, with little emotional content, merely showing what the product looks like.

There are several ads of this type. In print, there are straight announcement (in which there is simply a statement about the product or service), testimonial (in which someone tells about their own experience with the product), one picture (usually a drawing or painting) and two or more columns of print; and copy heavy (virtually all words, and a lot of them). In broadcast there is also straight announcement and testimonial, but also demonstration (in which the product is shown actually doing what it is purported to do).

The second basic way to present a sales message is emotionally. In an emotional presentation, the actual function of the product is often not its main selling point. Instead, there is a concentration on other aspects of the consumer's bundle of values: social, psychological, economic. For example, the presentation shows how the product or service enhances the audience's social life by improving their sex appeal or self-esteem, or how it will increase their earning power. (Bear in mind that reading about it (a cognitive exercise) may make it seem that these are intellectual appeals, but when presented using words with a high connotation content they are emotional.)

There are several types of ads that use the emotional presentation. For print these include the picture window (one large photograph, 60 to 70% of the ad, and one or two short columns of copy); color field (one photograph that fills the entire ad, with minimal, or even no copy, woven into the image); and lifestyle (one or more photographs showing people interacting with the product and enjoying "the good life" because of it).

For television, these include lifestyle (as above, but showing the people on film interacting with the product and enjoying the good life) and slice-of-life (a short playlet in which actors portray real people whose problem, be it social, psychological and/or economic, is solved by the product). These two types of commercials are particularly good for appealing to emotion, since they show 1) a lifestyle that the target audience of the product may wish, deep down inside, to live; or 2) they recognize themselves in the slice-of-life depicted, relate to the problem and wish to solve it as easily and quickly as depicted.

This book is concerned with just one of the above ways of processing and presenting sales messages: how advertising can be persuasive by appealing to people's emotions, their desires, the non-intellectual part of their bundle of values, and where those desires come from.

Go to Definition of

Advertising

Return to Taking ADvantage Contents Page

Return to Taflinger's

Home Page

You

can reach me by e-mail at: richt@turbonet.com

This page was created by Richard F. Taflinger. Thus, all errors, bad links, and even worse style are entirely his fault.

Copyright

© 1996, 2007 Richard F. Taflinger.

This and all other pages created by and containing the original work of Richard

F. Taflinger are copyrighted, and are thus subject to fair use policies, and

may not be copied, in whole or in part, without express written permission of

the author richt@turbonet.com.

Disclaimers

The information provided on this and other pages by me,

Richard F. Taflinger (richt@turbonet.com),

is under my own personal responsibility and not that of

In addition,

I, Richard F. Taflinger, accept no responsibility for WSU or ERMCC material or

policies. Statements issued on behalf of